Jobs and recovery monitor - Insecure work

The coronavirus pandemic has exposed the reality of insecure work in the UK.

Care workers, delivery drivers and shopworkers played a crucial role in keeping society going.

Meanwhile, in sectors like hospitality many insecure workers often found themselves without work.

This research shows:

- there are 3.6 million insecure workers in this country

- insecure work is pushing risk onto workers: more than half of insecure workers, including three quarters of people on zero-hours contracts had their hours cut due to the pandemic

- employers are increasingly scheduling and cancelling shifts at short notice with 84 per cent of zero-hours contract workers offered work at less than a day’s notice

- the main reason workers take on zero-hours work is because it is the only form available.

It is vital that the government urgently bring forward an employment bill and take steps to stamp out insecure work as the country begins its recovery.

Introduction

The last “Clap for carers” rang out on 28 May last year.

For several months many thousands, perhaps millions, of people stood on their doorsteps every Thursday evening applauding the care workers, delivery drivers and retail workers who kept the country going during lockdown.

The event drew much-needed attention to their insecure working conditions, too. Millions of these same workers were – and are – insecure workers. That means that they are on zero-hours contracts (ZHCs), in temporary or seasonal work or are self-employed workers earning less than the national minimum wage.

The clapping ceased more than a year ago. But the problem of insecure work remains unsolved and could even get worse if this economic downturn mirrors the last one.

This special edition of the TUC’s Jobs and Recovery Monitor lays bare the extent of insecure work in the UK and workers’ views of it.

Our latest analysis of official figures shows that 3.6 million people remain in insecure work. This figure that has remained stubbornly high since the Great Financial Crisis led to a spike in precarious work.

It means that one worker in nine has to endure insecure work.

The case is often made that many people prefer casual contracts. Sometimes it is argued that this gives workers the flexibility to balance their work and other responsibilities.

But polling conducted for the TUC among those shows that for most workers this flexibility is purely theoretical. It tells us that:

- employers are increasingly scheduling and cancelling shifts at the last minute, with 84 per cent of zero-hours contract workers offered work at less than a day’s notice

- the main reason workers take on zero-hours work is because it is the only work available

- insecure work is pushing risk onto workers: more than half of insecure workers, including three quarters of people on ZHCs had their hours cut due to the pandemic.1

.

There is widespread recognition that insecure workers need a better deal.

Successive manifestos from all major political parties promised action.

The Taylor review of modern working practices also proposed some solutions, though few have been implemented.2

.

And the current government announced an Employment Bill in its 2019 Queen’s Speech but has since taken the legislation off its latest Parliamentary agenda.3

.

There is a strong risk that, without action, there could be a repeat of past recessions where rising unemployment sees a deterioration in pay and conditions.

As a start we need to see:

- the abolition of zero hours contracts by giving workers the right to a contract that reflects their regular hours, at least four weeks’ notice of shifts and compensation for cancelled shifts

- penalties for employers who mislead people about their employment status

- genuine two-way flexibility by giving workers a default right to work flexibly from the first day in the job, and all jobs to be advertised as flexible

- greater union access to workplaces and stronger rights to establish collective bargaining so unions can negotiate secure working conditions.

Who are the country’s insecure workers?

TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey data shows that 3.6 million people are in insecure work.4

. This amounts to one in nine of the workforce.

When estimating the number of people in insecure work the TUC includes:

- those on zero-hours contracts

- agency, casual and seasonal workers (but not those on fixed – term contracts)

- the low-paid self-employed who miss out on key rights and protections that come with being an employee and cannot afford to provide a safety net for when they are unable to work.

|

Who is in insecure work? |

|

|

Zero-hours contract workers (excluding the self-employed and those falling in the categories below) |

876,800 |

|

Other insecure work - including agency, casual, seasonal and other workers, but not those on fixed-term contracts |

824,400 |

|

Low-paid self-employed (earning an hourly rate less than the minimum wage) |

1.91m |

|

TUC estimate of insecure work |

3.6m |

|

Proportion in insecure work |

11% |

Source: Labour Force Survey and Family Resources Survey. The total number in ‘insecure work’ includes (1) agency, casual, seasonal and other workers, but not those on fixed – term contracts, (2) workers whose primary job is a zero-hours contract, (3) self-employed workers who are paid less than the minimum wage. See footnote 4 for more details.

Occupation

Some of those of who kept the country going during the pandemic, despite their precarious working conditions, would be classed as platform workers. This includes delivery drivers and riders who stepped in when lots more people started to buy groceries and meals online.

And there are signs that some of the most notorious operators used the downturn to engage more staff.5

. This is despite recent court decisions that limit operators’ ability to duck their responsibilities for those who work for them.6

.

But insecure work is not new and it is certainly not limited to the digital economy.

Our analysis shows that nearly one in four (23.1 per cent) of those in elementary occupations including security guards, taxi drivers and shop assistants are in insecure work. It is the same for more than one in five (21.1 per cent) of those who are process, plant and machine operatives. Very large numbers of those in the skilled trades and caring, leisure and other service roles are also in precarious employment.

This compares to just one in 20 (5 per cent) of those in professional occupations and a similar proportion (5 per cent) of those who undertake administrative and secretarial work.

|

Proportion in insecure work – by occupation |

|

|

1: managers, directors and senior officials |

8.2% |

|

2: Professional |

5% |

|

3: Associate professional & technical |

8.7% |

|

4: Admin & secretarial |

5% |

|

5: Skilled trades |

19.7% |

|

6: Caring, leisure and other service |

18.7% |

|

7: Sales and customer services |

8% |

|

8: Process, plant and machine operatives |

21.1% |

|

9: Elementary |

23.1% |

Source: TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey and Family Resources Survey

Regions and nations

In every region of England and in Wales and Scotland a significant number of workers are in insecure work.

Our latest figures show that it is particularly prevalent in Wales (13.4 per cent) and in Northern Ireland (12.2 per cent).

In only two areas, Yorkshire and Humberside (9 per cent) and Scotland (9.8 per cent), are fewer than one in ten workers recorded as being in insecure work.

There is a risk that those regions that are seeing the greatest rises in unemployment as a result of the pandemic, will experience the greatest increase in insecure work.

Official figures show that London has been particularly hard-hit by the pandemic while the North East, which had relatively high levels of unemployment going into the pandemic, is still seeing high levels of joblessness.6 .

|

Proportion of insecure work by region |

|

|

North East |

10.7% |

|

North West |

10.9% |

|

Yorkshire and Humberside |

9.0% |

|

East Midlands |

10.3% |

|

West Midlands |

11.0% |

|

East of England |

13.7% |

|

London |

11.0% |

|

South East |

10.7% |

|

South West |

12.4% |

|

Wales |

13.4% |

|

Scotland |

9.8% |

|

Northern Ireland |

12.2% |

Source: TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey and Family Resources Survey

Gender

Patterns of insecurity vary significantly between men and women.

More men than women are in insecure work (2 million versus 1.6 million). This equates to 11.7 per cent of male workers and 10.6 per cent of females being in insecure work.

When it comes to employees (excluding the self-employed), women are more likely to be in insecure arrangements (6.5 per cent) compared to men (5.7 per cent).

However, men are significantly more likely to be in low-paid self-employment. There are 1.2 million men earning less than the minimum wage for their age group compared to 730,000. Although women who are self-employed are more likely to be low-paid.

|

Insecure work by gender |

|||||

|

|

Number |

Proportion |

|||

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

||

|

Total insecure employees |

794,276 |

906,851 |

5.7% |

6.5% |

|

|

Total in insecure work |

1,974,276 |

1,636,851 |

11.7% |

10.6% |

|

Source: TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey and Family Resources Survey

It is not yet clear what the relative impact of the pandemic and the associated economic slowdown on men and women will be.

Previous TUC analysis has shown that women are experiencing much higher levels of redundancies than in previous recessions, they continue to be more likely to be on furlough (particularly young women) and are overrepresented in industries that have been most severely hit by the pandemic.

For example, women have accounted for 60 per cent of the job losses in accommodation and food and 58 per cent of job losses in wholesale and retail, whereas in manufacturing men accounted for nearly 80 per cent of job losses.

Overall, job losses have been fairly evenly spread – based on workforce jobs data for employees, women have accounted for 52 per cent of job losses and men 48 per cent. This contrasts to previous recessions where men saw a bigger impact generally.7

. And women were struggling to retain their positions in the workforce. A TUC poll of 50,000 respondents published in January 2021 .

We also don’t yet know whether the disruption caused to people’s working patterns by lockdown measures, will have a long-term impact.

But the evidence is clear that women, whose earnings often take a hit due to parenthood[6], bore the bulk of the additional caring responsibilities caused by school and nursery closures.

By July 2020, mothers’ working hours were down by a quarter.8

And women were struggling to retain their positions in the workforce. A TUC poll of 50,000 respondents published in January 20219

, found that seven in 10 requests for furlough by working mothers were turned down and that a quarter were worried they would lose their job, either through being singled out for redundancy, sacked or denied hours.

These pressures continue as many children continue to be sent home from schools due to Covid infections.10

.

Some analysts speculate that the adoption of forms of hybrid home-and-office working, could harm women’s career progression if offices become more male-dominated. 11

This could lead to women relying more on forms of insecure work.

Young workers

Young people in insecure work have been particularly badly affected by the downturn.

Payroll data shows that 70 per cent of employee job losses between March 2020 and May 2021 were among under 25s.12

.

During the pandemic, the unemployment rate for Black and minority ethnic (BME) young workers has increased more than twice as fast as the unemployment rate for young white workers. And the number of 16-24 year-olds in work is lower than at any point during the 2008 financial crisis.13

.

By January 2021, 19 per cent of 18-24 year olds who were employed before the crisis had lost their job, 9 per cent were on furlough, and another 13 per cent had lost more than a tenth of their pay outside of furlough.

Young people who were in insecure work were most affected with more than a third (36 per cent) of 18-24 year olds on a zero-hours, agency or temporary contracts no longer working in January 2021.14

.

Much of this disproportionate impact on young people is because young workers are more likely to work in sectors like hospitality, retail and leisure. According to the IFS, employees aged under 25 were about two and a half times as likely to work in a sector that was shut down during the pandemic as other employees.15

.

One of the big challenges for the coming period is ensuring that those young workers who lost their insecure jobs during the pandemic find new – and more secure – work.

Ethnicity

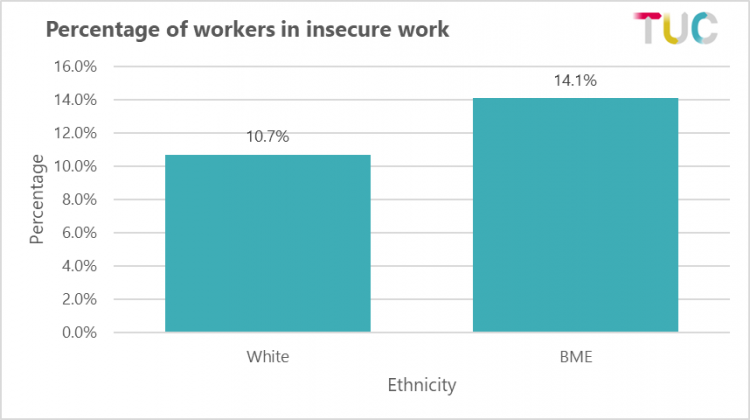

TUC analysis of official data shows that BME workers are far more likely than white workers to be in insecure work.

- 1 Polling for the TUC by GQR. Representative online survey of working Britain: adults 16+ who are in full- or part-time employment, weighted to national statistics on gender, age, region, social grade, ethnicity, work status, sector, and experience of furlough. Total sample n=2523. Fieldwork: 29th January – 16th February 2021

- 2 Taylor M. (2017). Good work: the Taylor review of modern working practices. Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy www.gov.uk/government/publications/good-work-the-taylor-review-of-moder…

- 3 Queen’s Speech 2019 www.gov.uk/government/speeches/queens-speech-2019

- 4 The total number in ‘insecure work’ includes (1) agency, casual, seasonal and other workers, but not those on fixed – term contracts, (2) workers whose primary job is a zero-hours contract, (3) self-employed workers who are paid less than the National Living Wage (£8.91). Data on temporary workers and zero-hour workers is taken from the Labour Force Survey (Q4 2020). Double counting has been excluded. he minimum wage for adults over 25 is currently £8.91 and is also known as the National Living Wage. The number of working people aged 25 and over earning below £8.91 is 1,910,000 from a total of 4,000,000 self-employed workers in the UK. The figures come from analysis of data for 2019/20 (the most recent available) in the Family Resources Survey and were commissioned by the TUC from Landman Economics. The Family Resources Survey suggests that fewer people are self-employed than other data sources, including the Labour Force Survey.

- 5 Nott, G (28 September 2020). “Deliveroo to double number of riders this year with 15,000 new hires”. The Grocer www.thegrocer.co.uk/hiring-and-firing/deliveroo-to-double-number-of-riders-this-year-with-15000-new-hires/648808.article. McCulloch, A (29 April 2021). “Uber to add a further 20,000 drivers in the UK”. Personnel Today www.personneltoday.com/hr/uber-to-add-a-further-20000-drivers-in-the-uk/

- 6 a b Carelli R et al (1 March 2021). “Landmark case recognises Uber drivers as workers. What are the implications for gig workers in the UK and beyond?” Fairwork fair.work/en/fw/blog/landmark-case-recognises-uber-drivers-as-workers-what-are-the-implications-for-gig-workers-in-the-uk-and-beyond/#continue

- 7 TUC (May 2021). Jobs and Recovery Monitor – Gender, issue 6. TUC www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-and-recovery-monitor-gend…

- 8 Slaughter, H. (14 June 2021). Labour market outlook Q2 2021, Resolution Foundation www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/labour-market-outlook-q2-2021/

- 9 TUC (2021), Working mums: Paying the price. TUC www.tuc.org.uk/workingparents

- 10 Burden, L et al (30 June 2021). “Working women suffer again as Covid wave empties UK classrooms”, Bloomberg www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-06-30/working-women-suffer-again-a…

- 11 Slaughter (14 June 2021)

- 12 Office for National Statistics (15 June 2021), Earnings and employment from Pay As You Earn Real Time Information, seasonally adjusted, ONS www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkin…

- 13 TUC (27 March 2021). Jobs and recovery monitor - update on young workers, issue 5, TUC www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-and-recovery-monitor-upda…

- 14 Sehmi, R and Slaughter H (13 May 2021). Double trouble, Exploring the labour market and mental health impact of Covid-19 on young people, Resolution Foundation www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/double-trouble/

- 15 Institute for Fiscal Studies (6 April 2020), Sector shutdowns during the coronavirus crisis: which workers are most exposed?, IFS

Nearly one in six (15.7 per cent) of BME men are likely to be in insecure work. Some 12.4 per cent of BME women are in the same position, and among employees (excluding the self-employed) BME women are the most likely group to be subjected to insecure work.

|

Those in insecure work by gender and ethnicity |

|||

|

Ethnicity |

Gender |

|

|

|

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

White |

11.1% |

10.3% |

10.7% |

|

BME |

15.7% |

12.4% |

14.1% |

Source: TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey and Family Resources Survey

Analysis previously published by the TUC has shown that 2.5 per cent of white men are on zero-hours contracts, compared to 4.1 per cent of BME men.

The highest proportions are found among BME women at 4.5 per cent, compared to 3.2 per cent of white women.16

The vast majority, some 65 per cent of all BME workers, say that their preferred job would be permanent and full-time. Just 1 per cent would opt for a zero-hours contract.17

BME workers place particular value on a contract with fixed hours. But they have little success in obtaining them. One in three BME workers in insecure work polled had asked for a fixed-hours contract but only one in three of those was successful. 18

Why workers are in insecure work

The argument made by those who support allowing employers to use insecure working arrangements is that they can offer two-way flexibility.

The worker gets to fit their work around their other commitments. The employer can have staff in for the hours they need them.19

But this overlooks both many workers’ experiences of the jobs market, and the desire among many employers to simply shift the risks of doing business onto their staff.

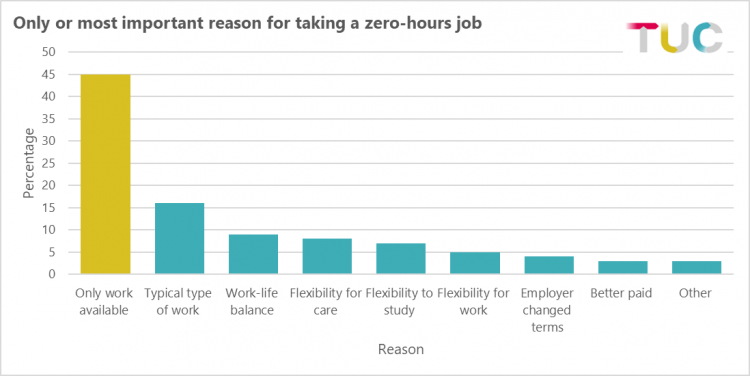

By far the most important reason that people take zero-hours contract work, for example, is because that is the only work available.

Some 45 per cent of respondents in a poll of 2,523 workers conducted by for the TUC said that this was the most important reason for them being on zero hours contracts while 16 per cent said it was the typical contract in their line of work. Just 9 per cent cited work-life balance as the most important reason.

- 16 T TUC/ROTA (2021). BME workers on zero-hours contracts, TUC https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/bme-workers-zero-hours…

- 17 GQR polling

- 18 GQR polling

- 19 Staffing Industry (2 June 2018).” UK – Matthew Taylor says zero-hours “can be positive””. Staffing Industry www2.staffingindustry.com/eng/Editorial/Daily-News/UK-Matthew-Taylor-says-zero-hours-contracts-can-be-positive-46319

Myth of two-way flexibility

Our polling shows that for large numbers of workers on zero-hours contracts, two-sided flexibility is a myth.

When polled, four in ten (42 per cent) of ZHC workers say that if offered shifts they either have to accept them (25 per cent) or they will be penalised (17 per cent), such as being denied future work.

BME workers are particularly likely to report they would be penalised for turning down shifts. Two in five BME workers report that they faced the threat of losing their shifts if they turned down work, compared to a quarter of white workers.

Indeed, despite the apparent benefits of flexibility, it is notable that mothers, who typically bear more of the caring burden, who are most likely to be offered shifts at short notice: more than two-thirds (67 per cent) report this happening often or from time-to-time. This compares to 57 per cent of fathers and 51 per cent of those with no children a home. Yet women are more likely than men to rank adequate notice of shifts as something that is important or very important to them.20

The nature of the shift in bearing the risk of fluctuations in demand from employer to worker is illustrated by the fact that over half of insecure workers and three quarters of people on ZHCs had their hours cut due to the pandemic.21

The impact of insecure work

One of the results of insecure work is that it further shifts power in the workplace towards the employer.

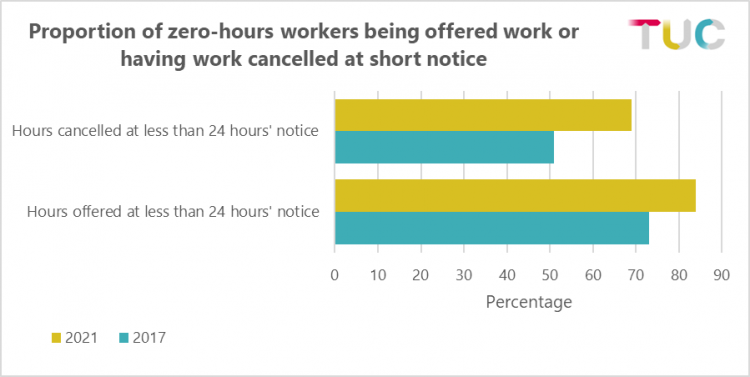

One way that employers build power and shift the risk of fluctuating demand onto workers is by scheduling and cancelling shifts at late notice. This makes it very hard for workers to budget or plan their private lives, yet our polling shows that it is increasingly prevalent.

Focusing just on zero-hours contract workers, 84 per cent of these workers have been offered shifts with such little notice, while more than two-thirds (69 per cent) have suffered short-notice cancellations.

In 2017 more than half (51 per cent) of zero-hours workers reported having had shifts cancelled at less than 24 hours' notice. And nearly three-quarters (73 per cent) had been offered work at less than 24 hours' notice.

This suggests an increased willingness among employers to force workers to shoulder the risks of changes in demand.

That is factor behind previous research by the TUC found that 55 per cent of those in insecure work had experienced a drop in their income since the start of the pandemic.22

The same research found that 44 per cent of those in insecure work have had to cut back spending, compared to a third of those in secure work.

- 20 GQR polling

- 21 GQR polling

- 22 TUC (2021). The impact of the pandemic on household finances, TUC www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/impact-pandemic-household-fina…

One result of this is that it is far harder for affected workers to budget and to manage responsibilities like childcare.

Workers have reported that their medical appointments and social events often have to be cancelled at short notice.23

It also further skews power relationships in the workplace. Workers become fearful about addressing legitimate employment issues.

For example, a separate set of polling for the TUC reveals that around three quarters (75 per cent) of those in secure work would feel comfortable raising an issue with their manager, compared to 60 per cent of those in insecure work.24

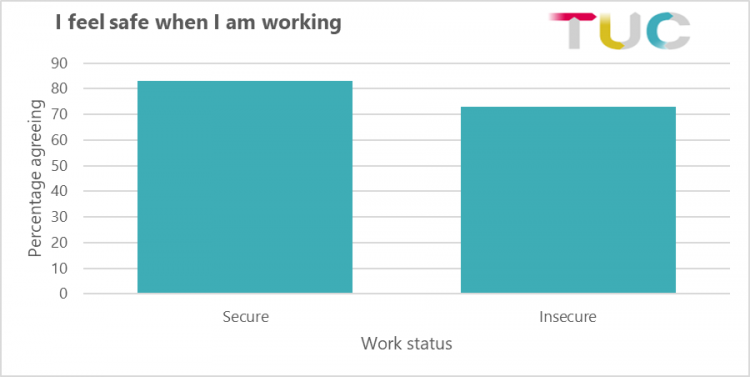

There is also a ten percentage point gap in the proportion of insecure and secure workers who feel safe at work. Some 73 per cent of insecure workers feel safe compared to 83 per cent of those in secure work.25

- 23 TUC (2018). Living on the Edge, TUC p. 35 www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/living-edge-0

- 24Polling by BritainThinks for the TUC. All respondents working full / part time May 2021 (n=1972), Nov 2020 (n=2,182); = Insecure (n=110); Secure (n=1851). BritainThinks’ definition of insecure workers does not include the self-employed.

- 25 BritainThinks

These power relationships feed through to pay and conditions. There is a notable gap in whether workers say they are paid fairly with just over half (51 per cent) of insecure workers feeling they receive a fair wage, ten percentage points lower than those in secure work.26

More than half (51 per cent) of those on insecure contracts say they receive no pay when off sick, compared to 5 per cent of those in secure arrangements, and those on insecure contracts are more likely to report one of the working conditions getting worse in the last year (39 per cent to 27 per cent).27

A recent TUC report set out the link between Covid-19 and insecure work, of which lack of sick pay is a contributing factor. That workers had little security over pay, often experienced peripatetic employment that brought them into contact with lots of people and were frequently subject to exploitative working conditions such as dirty working environments and shared cramped accommodation also played a part. 28

Conclusion – a recovery rooted in decent work

The pattern of previous recessions has been a rise in insecure work.

If unemployment rises, especially if the government proceeds with plans to wind down the furlough scheme, employers may feel better able to offer poor terms and conditions, in the knowledge that workers have little other choice.29

There are some factors pushing against this. The reopening of the economy should benefit those insecure workers whose workplaces shut down. And there is some sign that employers are struggling to hire staff in sectors like hospitality which could push up wages and improve conditions.30

Meanwhile, decent work is critical for a good economic recovery. The OECD argues that countries with policies and institutions that promote job quality, job quantity and greater inclusiveness perform better than countries where the focus of policy is predominantly on enhancing (or preserving) market flexibility.31

This means we shouldn’t again place blind faith in market forces to deliver a fair outcome to workers.

Rather than wait until the economy has picked up again, now is the ideal time for the government to bring forward its long-promised Employment Bill.

Here are some measures that should feature:

A ban on zero-hour contracts.

This report shows that zero-hours contracts are highly exploitative. There should be an effective ban on them by giving workers the right to a contract that reflects their regular hours. This would also benefit those on short-hours contracts (such as eight hours a week) who regularly work much longer. This right should be coupled with rules obliging employers to give at least four weeks’ notice of shifts and compensation to workers for shifts that are cancelled at late notice.

Penalties for employers who mislead people about their employment status

Employment status is both complex and hugely important. Those who are “workers” are entitled to the minimum wage and paid holiday. Employee status brings with it other protections, such as parental rights.32

That is why workers are prepared to go to court to establish their status in the face of employer intransigence.

There has long been concern about the number of employers who seek to save money and gain an advantage over their competitors, for instance by insisting to their workers that they are actually self-employed contractors. 33

There should be a statutory presumption that all individuals will qualify for employment rights unless the employer can demonstrate they are genuinely self-employed. If they mislead their workers, they should face penalties.

Give workers a default right to work flexibly from the first day in the job, and all jobs to be advertised as flexible.

One driver of insecure work is the inability of many workers to secure flexible working options in other roles, particularly if their role cannot be done at home.

Recent research published by the TUC showed that those who cannot work from home are significantly more likely to be denied flexible working options by employers after the pandemic.

Our survey found that one in 6 (16 per cent) employers say that after the pandemic, they will not offer flexible working opportunities to staff who could not work from home during the pandemic. This compares to one in 16 (6 per cent) saying they will not offer flexible working opportunities to those who did work from home in the pandemic.

Four out of five (82 per cent) of workers say that they want to take up some form of flexible working in the future. But only half of workers (54 per cent) say they have the right in their current job to request a change to their regular working hours to fit around other commitments.

Unions to be given a right to access workplaces and improved collective bargaining rights

Ultimately the best way of paving the way for greater security at work is to extend the protection afforded by trade unions.

Throughout the pandemic unions have worked hard at national, 34

sectoral[35

and workplace level 36

to protect workers and ensure the economy kept functioning.

They have also secured important improvements to workers’ terms and conditions, including for those who are regarded as insecure workers.

UNISON won a fight for paid travelling time for care workers who were getting as little as £4 a hour.37

At supermarket chain Morrisons, Usdaw negotiated a minimum rate of £10 an hour. 38

A lengthy court battle led by unions over whether drivers at Uber had worker status, and therefore some key workplace rights, was finally settled in the workers’ favour.39

And as a result the GMB gained recognition there.40

But the UK has extremely restrictive trade union laws and it is hard for unions to organised at workplaces in remote locations or where an employer is hostile.

That is why we argue for unions to be given a right to access workplaces to tell workers about the benefits of union membership and collective bargaining (following the system in place in New Zealand).

This should be accompanied by new rights to make it easier for working people to negotiate collectively with their employer, including simplifying the process that workers must follow to have their union recognised by their employer for collective bargaining and enabling unions to scale up bargaining rights in large, multi-site organisations.41

- 26 BritainThinks

- 27 BritainThinks

- 28 TUC (2021). Covid-19 and insecure work, TUC www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/covid-19-and-insecure-work

- 29 Comemetti, N et al (2021). Low Pay Britain 2021, Resolution Foundation www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/low-pay-britain-2021/

- 30 Skopoletti, C (27 June 2021). “‘We literally don’t get time to take breaks’: How staff shortages are affecting hospitality workers”. The Independent www.independent.co.uk/news/business/brexit-covid-hospitality-staff-shor…

- 31 OECD (2017). Economic Surveys: United Kingdom 2017, www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/eco_surveys-gbr-2017-en/1/2/1/index.html?it…

- 32 TUC (2018). Taylor review: employment status, TUC www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/TUCresponse-statusconsultation.pdf

- 33 Citizens Advice (14 June 2017). “10 things employers say to mislead workers about their rights”. Citizens Advice www.citizensadvice.org.uk/about-us/about-us1/media/press-releases/10-things-employers-say-to-mislead-workers-about-their-rights/; Citizens Advice (2015). Neither one thing nor the other, Citizens Advice www.citizensadvice.org.uk/Global/CitizensAdvice/Work%20Publications/Nei…

- 34 Economist (16 May 2020) “Trade unions are back”, Economist www.economist.com/britain/2020/05/16/trade-unions-are-back

- 35 Usdaw (6 May 2020). “Usdaw and BRC working together on how the retail sector can be safely brought out of lockdown”, Usdaw www.usdaw.org.uk/About-Us/News/2020/May/Usdaw-and-BRC-working-together-…

- 36 Unite (8 April 2020). “Rolls-Royce coronavirus package puts health & safety centre stage, says Unite”, Unite www.unitetheunion.org/news-events/news/2020/april/rolls-royce-coronavir…

- 37 Mackenzie, N (15 September 2020). “Unison: Care workers who made £4 an hour awarded in £100,000 court case”, BBC www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-54154922

- 38 Usdaw (13 January 2021). “Morrisons pay deal: Usdaw negotiates a £10 per hour basic rate in a major step forward for the union's New Deal for Workers campaign”, Usdaw www.usdaw.org.uk/About-Us/News/2021/Jan/Morrisons-pay-deal-Usdaw-negoti…

- 39 De Stefano, V (2 March 2021). “Regulation is not an À la Carte menu: insights from the Uber judgment”, UK Labour Law Blog uklabourlawblog.com/2021/03/02/regulation-is-not-an-a-la-carte-menu-insights-from-the-uber-judgment-by-valerio-de-stefano/

- 40 GMB (26 May 2021). “Uber and GMB strike historic union deal for 70,000 drivers”, GMB www.gmb.org.uk/news/uber-and-gmb-strike-historic-union-deal-70000-uk-dr…

- 41 These proposals are set out in TUC (2019). A stronger voice for workers, TUC www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/stronger-voice-workers

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox