International justice day for cleaners and security guards

The Covid-19 crisis has served as a stark reminder of what work is essential. Cleaners and security guards have been on the frontline during the crisis. They have put themselves and their families at risk to keep us clean and safe. Yet they continue to be badly paid, insecure and undervalued.

The crisis must mark a turning point. Our claps for key workers during the height of the crisis must be turned into action to bring justice to cleaners and security guards. This international justice day, the TUC are calling for:

- Fair pay and decent contracts for all cleaners and security guards – including a £10 an hour minimum wage, an end to zero hours contracts, fair notice of shifts, a decent pension and reasonable rights to holiday, sick leave and sick pay.

- Safe working and PPE – full access to appropriate PPE and testing and published risk assessments.

- Insourcing and responsible procurement to restore terms and conditions - a new approach to commissioning and public procurement that makes in-house provision the default and only contracts out when there is a demonstrable public interest case for doing so and in a way that enforces high service delivery and employment standards.

- Recognition, dignity and respect for cleaners and security guards as key workers – the previous measures will go a long way to show our appreciation of their sacrifices during Covid. The best way to ensure continued dignity and respect after the clapping has stopped is to support cleaners and security guards’ ability to self-organise by ensuring access to workplaces for unions.

Download full report (pdf)

International Justice Day for Cleaners and Security Guards is held each year in memory of a group of Los Angeles janitors being beaten up by the police during a peaceful demonstration against their contractor. This year marks the 30th anniversary of the incident and comes in the midst of the Covid-19 crisis that has seen cleaners and security guards on the frontline in protecting us, often at great personal risk to themselves. Security guards are more likely to die from Covid-19 than any other profession.

Justice for cleaners and security guards means:

- Fair pay and decent contracts for all cleaners and security guards

- Safe working conditions and adequate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

- Insourcing and responsible procurement to restore terms and conditions

- Recognition, dignity and respect for cleaners and security guards as key workers and appreciation of their sacrifices during Covid-19

Executive Summary

We all rely on cleaners and security guards to keep our workplaces and social spaces clean and safe. Yet despite their essential contributions, cleaners and security guards are grossly undervalued, under-appreciated and under-paid. Widespread outsourcing in both sectors has put pressure on pay and working conditions.

Compared to the workforce as a whole, they are lower paid and more likely to be on zero hours contracts. BAME people are disproportionately represented in both professions, which are also highly gendered, meaning that poor working conditions of cleaners and security guards compounds wider labour market inequalities. For example,

- 80% of cleaners are women while 84% of security guards are men

- 16% of cleaners and 26% of security guards are BAME workers, compared to 12% of the all workers

- 47% of cleaners and 43% of security guards are over the age of 50, compared to 30% of all workers

- Security guards earn £2.98 an hour less than the median hourly pay and cleaners earn £3.98 less

- Cleaners and security guards earn less in the private sector compared to the public sector – nearly £3 per hour less in the case of security guards

- Cleaners and security guards are at least twice as likely to be on zero hours contracts compared to the workforce as a whole. Most of these zero hours contracts are in the private sector.

The Covid-19 crisis must mark a turning point. It is time to show proper appreciation for the enormous contribution that cleaners and security guards make to society, by giving them better pay and working conditions as well as dignity and respect.

Labour market conditions

There are approximately 450,000 people employed as cleaners & domestics in the UK and approximately 150,000 people employed as security & related occupations.

Gender

Both roles are highly gendered with women making up 80 per cent of cleaners and domestics and men making up 84 per cent of security guards.

Ethnicity

There are also a higher proportion of BAME workers employed in both occupations than the average employment level for BAME workers in general. BAME workers make up 12 per cent of the employee population, whereas they make up 16 per cent of cleaners and domestics and 26 per cent of security guards and related occupations, meaning they are more than twice as likely to be working in security.

Age

There are a higher number of employees over the age of 50 working as cleaners & domestics and in the security guard & related occupations sector.

Pay

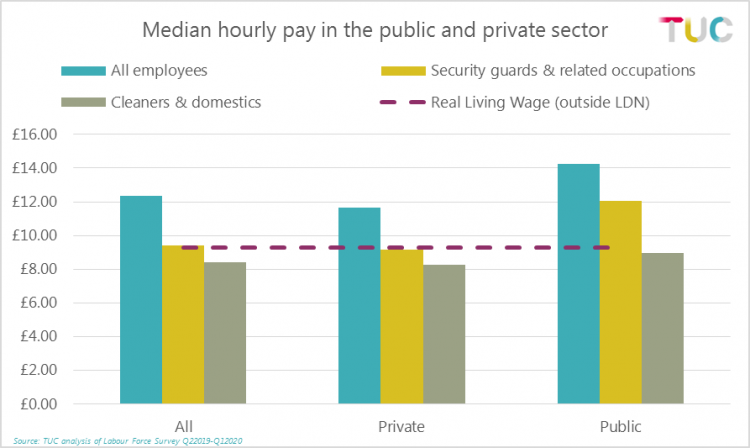

According to latest pay data from the Labour Force Survey, the median hourly pay for all employees in the UK is around £12.38 per hour. Both cleaners and security guards earn significantly less than this, with security guards earning £2.98 an hour less (median hourly pay £9.40) and cleaners earning £3.98 less (median hourly pay at £8.40). The median pay for cleaners is also below the real living wage (outside of London) of £9.30.

Previous pay data from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings for 2019 finds that 60 per cent of cleaners and domestics and 40 per cent of security guards earn less per hour than the recommended real living wage (£9.30).

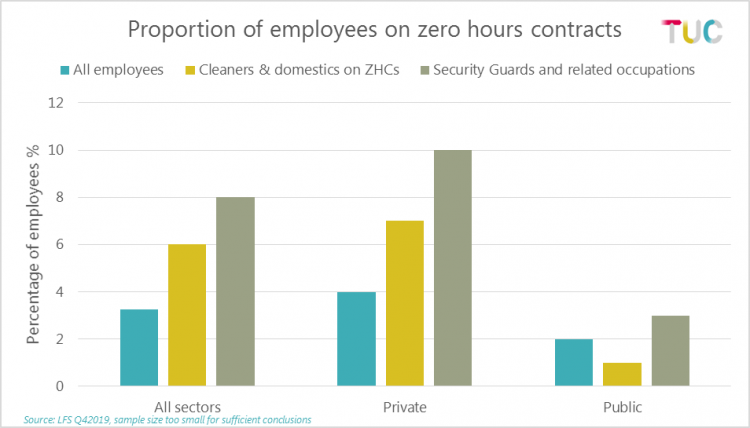

Zero hours contracts

Cleaners and security guards are at least twice as likely to be on zero hours contracts than the workforce as a whole. Around 6 per cent of cleaners and domestics and around 8 per cent of security guards and related occupations are estimated to be on zero hours contracts compared to 3 per cent of all workers.

Covid-19 mortality rates

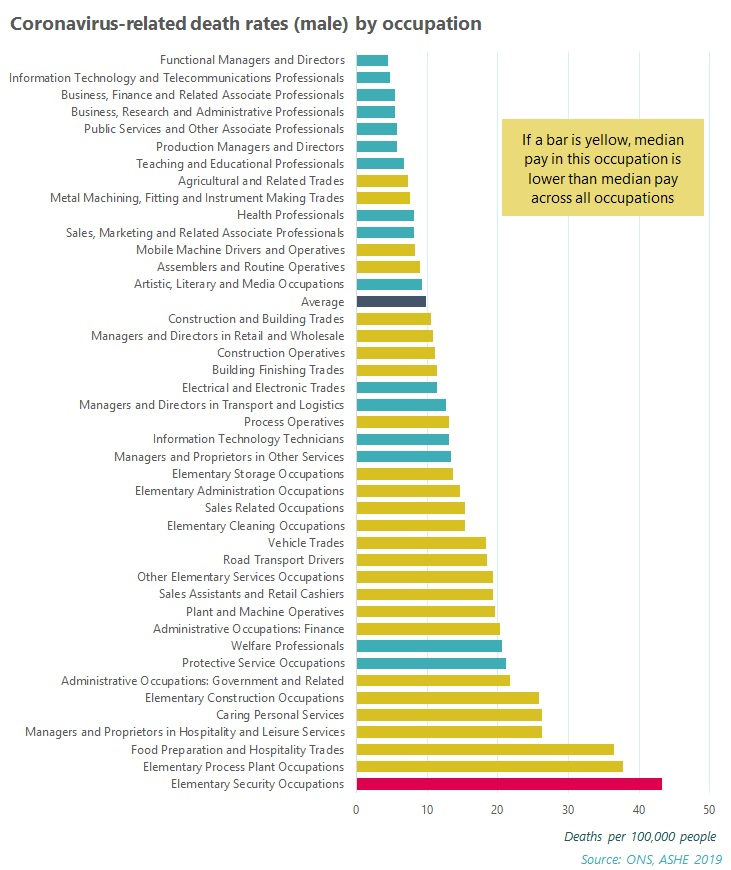

Recent data from the ONS on Covid-19 mortality rates showed a strong correlation between low pay occupations and Covid-19 mortality rates. This was particularly the case for men working in elementary occupations, where the mortality rate was four times higher than men working in professional occupations.

Elementary security occupations had the highest mortality rate amongst males of all occupations, with a mortality rate of 45.7 per 100,000.

Outsourcing

Many organisations now outsource their cleaning and security functions to specialist subcontracting firms. A number of studies have found that outsourcing and subcontracting are associated with a deterioration in pay, terms and conditions for the workforce and with lower quality service delivery. 1

The major driver for outsourcing is cost reduction. This means that contracts are often awarded to the lowest cost bid, which in turn puts pressure on cleaning and security companies to force down costs, the bulk of which are labour costs. An EHRC investigation into outsourcing of cleaning services, for example, found that “procurement puts pressure on a cleaning firm’s pay and work intensity requirements which can mean low quality service, low work commitment and high turnover of staff.” 2

Their findings are borne out elsewhere. For example, a study in the US found that the “penalty resulting from a worker being assigned to an outsourced job as opposed to an in-house one of 4-7 percent for janitors and 8-24 percent for guards.” 3 A study of onsite outsourcing in Germany found it was associated with a 10% fall in wages over a 5-10 year period. Two studies of the care sector in England found that services contracted out to private providers performed worse across pay, numbers of zero hours contracts, skill levels and staff retention and turnover compared to inhouse provision by local authorities.4

Short-term contracts are subject to regular renewal of short-term contracts and budget negotiations, which means that “pay and the organisation of work is always under pressure” and such contracts “frequently fail to encourage positive relationships developing between clients and cleaning firms and contribute to these pressures.” 5

Contracting out can also create barriers in the workplace, with outsourced workers not only treated different but perceived differently to those directly employed in the same workplace. For example, the EHRC found that “workers did not always feel they are afforded the same dignity and respect shown to others in the workplace” and that “workers spoke of being ‘invisible’ and ‘the lowest of the low’”. 6 91 per cent of outsourced cleaners working on the London Underground said they would rather be employed in-house. 7

It is not just workers who suffer when services are contracted out, service quality often does too. This may be due to lack of specialist knowledge and expertise in areas such as health hygiene 8 as well as wider issues of cost cutting and high staff turnover associated with outsourcing. 9 A recent study found that subcontracting of cleaning services in the NHS resulted “in lower cleaning standards as evaluated by patients and higher hospital-associated infection rates as indicated by MRSA rates.” 10 In a survey of London Underground cleaners carried out by the RMT union, 78 per cent believed passengers would benefit more if their jobs were brought in-house. 11

Extent of outsourcing

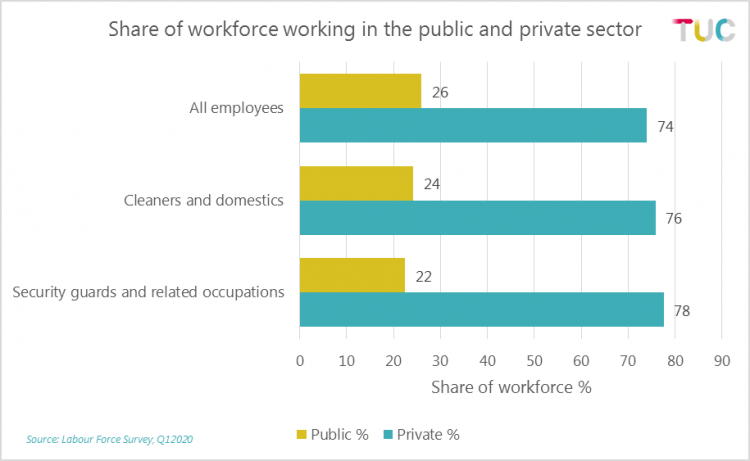

The data does not show the extent of outsourcing in either sector, so we use the share of workers employed in the private sector as a proxy. It should be noted that this will only roughly approximate the share of the workforce that is outsourced because it will include cleaners and security guards directly employed in the private sector as well as those subcontracted from both public and private organisations.

According to this method, the majority of both of both professions - 76 per cent of cleaners and 78 per cent of security guards – are employed in the private sector. Both occupations are broadly in line with the employment split nationally, though have a slightly higher incidence of private sector employment, as the chart below shows.

- 1 See Ole Helby Petersen, Ulf Hjelmar, Karsten Vrangbæk & Lisa la Cour (2011) “Effects of contracting out public sector tasks – A research-based review of Danish and international studies from 2000-2011,” AFK for an overview of international studies and TUC (2015) “Outsourcing Public Services” for UK evidence.

- 2 Equality and Human Rights Commission (2014) “The Invisible Workforce: Employment Practices in the Cleaning Sector

- 3 The Smith Institute (2014) “Outsourcing the Cuts”

- 4 The Smith Institute (2014) “Outsourcing the Cuts” and Whitfield, D (2015) “The New Health and Social Care Economy; Sefton MBC, Liverpool and Greater Manchester City Regions and North West regional economy”

- 5 Equality and Human Rights Commission (2014) “The Invisible Workforce: Employment Practices in the Cleaning Sector,” European Services Strategy Unit/New Directions

- 6 Equality and Human Rights Commission (2014) “The Invisible Workforce: Employment Practices in the Cleaning Sector”

- 7 RMT (2020) “Dirty Work ABM and the outsourcing of London’s Underground cleaners”

- 8 Elkomy, S., G. Cookson and S. Jones (2019) “Cheap and Dirty: The Effect of Contracting Out Cleaning on Efficiency and Effectiveness,” Public Administration Review, Vol. 79, Iss. 2, pp. 193–202

- 9 Equality and Human Rights Commission (2014) “The Invisible Workforce: Employment Practices in the Cleaning Sector”

- 10 Elkomy, S., G. Cookson and S. Jones (2019) “Cheap and Dirty: The Effect of Contracting Out Cleaning on Efficiency and Effectiveness,” Public Administration Review, Vol. 79, Iss. 2, pp. 193–202

- 11 RMT (2020) “Dirty Work ABM and the outsourcing of London’s Underground cleaners”

Pay

We showed above how pay in both sectors is lower than pay in many other occupations. Here we look in more detail at how pay differs in the public and private sector as a way to examine the impact of outsourcing.

Cleaners and domestics and security guards in the private sector are paid less than their public sector counterparts. Particularly security guards, where the median hourly pay in the private sector is nearly £3 less than in the public sector (£9.15 and £12.05 respectively).

Insecurity

Zero hours contracts are driven by the private sector, where 10 per cent of security guards and 7 per cent of cleaners are likely to be on zero hours contracts.

Justice for cleaners and security guards

Unions are already playing a vital role in securing better deals for cleaners and security guards:

- On 15 May 2020, UNISON reported that the Medirest private company will give its 2,200 staff, who provide cleaning, portering and catering services in NHS hospitals across England, a pay increase of an average of 5 per cent from the beginning of June. The lowest pay rate will rise from £8.75 to £9.2 an hour, bringing their pay in line with NHS staff doing similar jobs.

- On 23 April 2020, the GMB achieved a commitment from outsourcing company ISS to pay cleaners at Lewisham Hospital the London Living Wage.

- Civil service unions, including PCS, secured agreement that all staff working on civil service outsourced contracts will receive full pay for COVID-19 related absences, including self-isolation, shielding, and time off to for caring responsibilities

- 900 outsourced UCL staff are now entitled to the same pay, pension, sickness allowances and annual leave rights as directly employed workers doing the same jobs as the result of a deal brokered by Unison last year.

- Last year, Unite secured a package that included increased pay rates, improved sick pay arrangements, and new PPE equipment for security staff at Southampton General Hospital.

There is mounting evidence that “the direction of travel is no longer in favour of widespread outsourcing of public services” (APSE) as hospitals, local authorities and other public bodies increasingly turn to insourcing as a way of improving service delivery. There is also growing awareness among procurers and subcontractors alike that paying a living wage and improving terms and conditions will help reduce staff turnover and absenteeism. However, we need to go further.

The Covid-19 crisis has served as a stark reminder of what work is essential. Cleaners and security guards have been on the frontline during the crisis. They have put themselves and their families at risk to keep us clean and safe. Yet they continue to be badly paid, insecure and undervalued.

The crisis must mark a turning point. Our claps for key workers during the height of the crisis must be turned into action to bring justice to cleaners and security guards. This international justice day, the TUC are calling for:

- Fair pay and decent contracts for all cleaners and security guards – including a £10 an hour minimum wage, an end to zero hours contracts, fair notice of shifts, a decent pension and reasonable rights to holiday, sick leave and sick pay.

- Safe working and PPE – full access to appropriate PPE and testing and published risk assessments.

- Insourcing and responsible procurement to restore terms and conditions - a new approach to commissioning and public procurement that makes in-house provision the default and only contracts out when there is a demonstrable public interest case for doing so and in a way that enforces high service delivery and employment standards.

- Recognition, dignity and respect for cleaners and security guards as key workers – the previous measures will go a long way to show our appreciation of their sacrifices during Covid. The best way to ensure continued dignity and respect after the clapping has stopped is to support cleaners and security guards’ ability to self-organise by ensuring access to workplaces for unions.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox