Challenging Amazon report - Amazon and local government

We have outlined the many ways in which Amazon creates its unfair advantage. Rather than building a healthy and fair system, both online and within the communities it operates in, often, its practices stifle workers’ rights, fair competition and the ability of governments to hold it accountable.

Therefore, a key challenge is holding Amazon to account and ensuring that its growing presence in the UK is not accompanied by the undermining of communities, local governance and workers’ rights

This is particularly important when the Covid-19 pandemic and economic downturn could strengthen the hand of those companies offering to bring jobs to an area.

As part of our research for this report we looked at Amazon’s relationship with local government to illustrate its current power and growing influence and its impact on local employment conditions. We suggest areas for change in order to give local authorities more agency when dealing with Amazon and make Amazon more accountable.

The pressure on local authorities to keep existing jobs and bring new jobs into their areas, as well as find ways to support their already cash-strapped budgets is going to be immense. Likewise, while Amazon continues to benefit from the pandemic, other retailers, faced with an economic crisis and adapting to the continued risk to public health, will struggle to keep afloat.

We also know that our high streets are changing and how they will look and be used in the future is uncertain. This challenge is not new. But the Covid-19 pandemic has almost certainly exacerbated existing trends towards a greater share of sales coming from online as opposed to bricks and mortar stores, making the need to support local government in developing sustainable high street renewal and jobs even more urgent.

By focussing on local government relationships with Amazon to date, we hope to contribute to the discussion about how we can support authorities in bringing good employment and fair working practices to their communities; ensure that social value and ethical supply chains are embedded throughout the employment and procurement processes; and enable local authorities to get the best outcomes for their citizens and communities.

What we did

To build a picture of Amazon’s reach into local government and the agency local authorities have when dealing with it, we looked at two aspects of Amazon’s presence in the UK – employment and procurement.

First, we sent Freedom of Information requests (FOIs) to 55 local authorities that have an Amazon site (distribution centre, development centre or delivery hubs and lockers) asking the extent to which local authorities had had any oversight or input into establishing Amazon in the area, either through the planning process or through other negotiations and engagement with Amazon.

We specifically wanted to know if any consideration or assurances had been given regarding employment rights and fair working practices (such as union recognition, fair notice periods, living wages and health and safety).

Second, we wanted to know the extent to which local government mirrors central government in increasing their spend with Amazon, particularly through the award of public procurement contracts. Here we commissioned research jointly with GMB to look at procurement contract awards and day-to-day spending. We followed this up by sending FOIs to individual local authorities that had particularly high spending levels and/or had awarded significant procurement contracts to Amazon, asking whether any weighting had been given to social value criteria (see box 4) in the procurement process as required by the public contracts regulations 2015. And, if so, what criteria were used and how Amazon demonstrated its commitment to them.

Box 4: Social value in the procurement processSocial value in procurement and commissioning refers to using the leverage public bodies have as purchasers of goods and commissioners of services to help to achieve economic, social and environmental goals. Within this broader strategy, public procurement can be used to promote good work through the contracting process. Permissive legislation, including the Public Services (Social Value) Act, the Public Contracts Regulations 2015, the Equality Act 2010 and public procurement legislation in Wales and Scotland provides the scope for more action on good work – enabling public bodies to move away from price-based competition and incorporate broader social, environmental and employment considerations where this is relevant to the nature of the contract. And while this potential has yet to be fully exploited, we are seeing things moving in the right direction. We believe public procurement can be a key tool in promoting good work as part of a wider strategy across government that could also include:

|

What we found out

Employment

To date we have had 47 responses to our FOIs. We began this research in early March, just before the coronavirus pandemic. This responses to our requests.

Of the responses we have received, a couple of local authorities had had some significant engagement with Amazon regarding employment.

One local authority had worked with Amazon to draw up an employment and skills plan as part of a planning condition for Amazon to occupy the premises in 2017. The city council’s skills and growth manager worked with Amazon to draw up the plan. Once the plan was agreed the City Council’s ‘Employment Hub’ supported local recruitment of staff including hosting recruitment events.

The employment and skills plan included commitments to:

- promoting accessible opportunities for local people

- use training to support skills development and a qualified, competent, motivated workforce

- engage with local business and community needs

- work with local actors including the council, job centres and other employment schemes, maximising the legacy benefit through long term employment.

The plan also commits to training and apprenticeships through Amazon’s apprenticeship scheme as well as monitoring on progress through annual updates for the first five years. We followed up on this with another FOI requesting to see any available progress reports. Unfortunately, Amazon owns this data so the local authority in question were unable to share these with us.

Similarly, another local authority had engaged with Amazon through their Skills Company with the aim of supporting the council and neighbouring authorities to get long-term unemployed residents back into the workplace. Running alongside Amazon’s usual recruitment process, a pre-employment course was provided to residents in order to prepare them for applications and Amazon recruitment events.

Amazon also worked with this local authority to produce an employment and skills plan which aims to:

- raise aspirations and engagement, promoting participation in education and training

- support education providers to design relevant curriculum and training and align career choices and guidance with employment available

- provide opportunities such as employment, supported employment, work experience, apprenticeships, traineeships, internships, mentoring and volunteering for a range of ages and abilities

- support the local labour force by training residents to give them skills and qualifications needed

- engage with local businesses, develop local supply chains to proactively source local suppliers; buy local goods, trades and services

- engage with the local community to address specific local needs

- build a sustainable relationship and legacy between all stakeholders including the developer/owner, employers, partners, local community, businesses and residents.

Again, when we followed up with another FOI regarding the monitoring of this plan, the council confirmed that responsibility for implementation and therefore monitoring lay with Amazon.

Another council had liaised with Amazon and other employers through participation in local jobs fairs and their employment support team worked in conjunction with the DWP to invite Amazon to jobs fairs and Job Centre meetings with job seekers between April and October 2019. Amazon also met with a local works project to discuss engagement with schools to deliver coding sessions.

Other responses suggested that local authorities had had little engagement or agency regarding Amazon as they established themselves in their areas. One FOI response said:

“The client signed an NDA with their agent CBRE, who did not disclose to us who their client was until after the land acquisition deal was signed.”

Others suggested their involvement typically stemmed from health and safety complaints, whereby councils would only engage once a complaint is received or incident has occurred.

Some councils made clear that employment rights or working practices are not typically part of the planning process, with one response stating that the council held “…no information regarding this. Employment rights are to do with the company itself".

What does this tell us?

Our research suggests that where there has been engagement with Amazon on employment, it has focussed more on job creation and developing skills to meet Amazon’s criteria. Job creation is an important goal for local authorities, and it is to be commended that some councils have managed to build some form of relationship and have some input through employment and skills plans. But evidence suggests that Amazon controls the monitoring of these commitments so there is no way of knowing if they are delivering on their promises. More needs to be done to ensure that councils can guarantee that good quality jobs, employment rights and accountability from Amazon (and others) are part of the deal as well as other social value goals.

Another theme to emerge from the research is the inconsistency and complexity of the planning system. While there are examples of councils making employment and skills part of the criteria of the planning process, this is not consistent and as discussed does not necessarily focus on employment rights and fair working practices. This can be further complicated by the number of parties involved, who owns the land and whether Amazon is directly leasing from the council or through a third party, as demonstrated by one response which stated:

“The site is privately owned and so we have no authority to ask that the criteria stated was agreed to by Amazon as they are a private tenant and any agreements were between Amazon and the developer. We cannot confirm or deny that they have implemented any of the stated criteria, as again we have no authority to request this information.”

As we outlined in chapter two, there are many reports of poor employment practices at Amazon from bogus self-employment of drivers, employees being fired with no consultation, extensive surveillance, gruelling working conditions that jeopardise people’s health, health and safety violations in general and particularly during the coronavirus crisis and actively working against unionisation. As Amazon expands its workforce in the UK it is vital it can be challenged to do better to give workers security, safety and dignity at work.

Procurement and spending

Amazon’s reach into local government is not yet as widespread as it is at central government level.

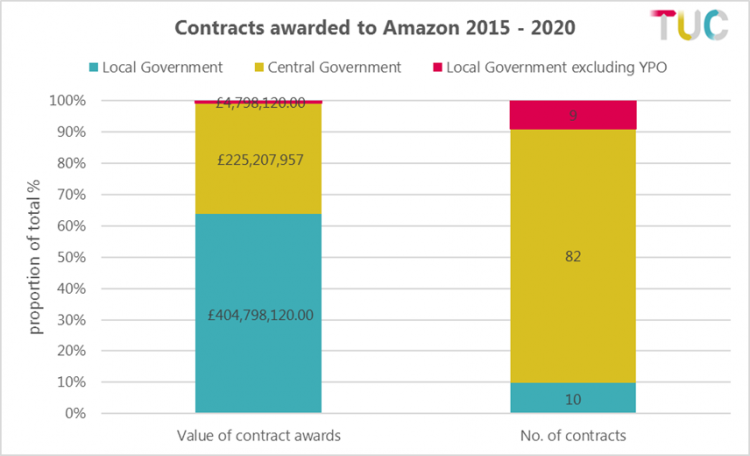

Research commissioned with GMB from Tussell Ltd, showed that between 2015 and May 2020, Amazon were awarded 92 public sector contracts (for both national and local government) with a lifetime value of up to £630 million pounds. The majority of these have been awarded since 2017 and are for Amazon Web Services (cloud related infrastructure and services), with a notable exception of the Yorkshire Purchasing Organisation (YPO) framework agreement, potentially worth up to £400 million over the life of the contract for the creation of a digital marketplace for the 13 local authorities that are covered by the YPO.[1]

More common at local level is smaller spending through the Amazon marketplace (which does not have to go out to tender as it is below a certain threshold), albeit the value is low.

Contract awards

Central government has awarded 82 contracts (89 per cent) to Amazon over this period with a lifetime value of over £225 million. In contrast local government has awarded only 10 contracts, but due to the YPO contract the potential lifetime value of these awards is nearly £405 million. Excluding the YPO, Amazon has still gained nearly £5 million in contract awards from 4 local authorities and TFL.

Public Contract awards to Amazon

As the YPO contract is a sizeable contract at local government level we also sent a Freedom of Information Request to establish to what extent social value criteria and ethical trading standards in the supply chain had been considered.

In response to our request the YPO referred us to the VEAT Notice (voluntary ex-ante Transparency notice)[1] and PIN (Prior Information Notice)[2] made publicly available and to section 32 of the Public Contracts regulations[3].

The Original PIN states in section 11.2.3:

Potential providers would need to meet the following criteria in order to participate in the pre-market engagement phase, and move on to the full tender process:

- single point of access for suppliers and customers,

- clarity of customer order, payment, fulfilment, and returns options,

- an established B2B marketplace presence,

- a diverse range of products which includes but is not restricted to curriculum resources,

- management of procurement authorisation levels,

- comprehensive cyber security.

The VEAT notice states that following the publication of the Prior Information Notice, the YPO only received one ‘compliant expression of interest’ and that:

“The proposed contractor, being an established mature B2B marketplace provider with a range offering of over 1 000 000 products from thousands of sources, is both the only contractor capable of achieving the desired economies of scale required to bring all spend within one portal to generate significant cost benefits to YPO's permissible users and the only viable contractor currently operating in the market for the products and service requirement requested.”

So, Amazon was considered the only viable option for this type and scale of contract. Under section 32 of the Public Contracts Regulations, contracting authorities may award public contracts by negotiated procedure without prior publication in some circumstances, including where the works, supplies or services can be supplied only by a particular economic operator due to the absence of competition for technical reasons.[4]

This demonstrates very clearly the challenge posed by Amazon’s scale and scope. It has built its effective marketplace monopoly by providing a platform for third party sellers, gathering information and using it to grow its own product range as well as making it the only viable place for sellers to operate through. In doing so, it has now become so big that no other platforms can compete with it in terms of scale, therefore crowding out the competition and making organisations feel there is little choice in who they deal with. It has become something of a self-fulfilling procurement prophecy.

In responding to our FOI request the YPO were able to give us sight of a redacted copy of its framework agreement as well as a copy of their Ethical Trading Policy.

The Ethical Trading Policy states the policy aims as:

- ensuring that social, ethical, environmental and economic impacts are considered in decision-making throughout the organisation

- providing a single reference to legal and regulatory requirements for ethical business practice

- setting baseline standards for procurement decisions

- providing a framework for other social, environmental and ethical activity

- committing to management review and continuous improvement of ethical practices.

The document states that the policy will achieve this by, committing to several measures as a minimum, including:

- committing to high ethical standards in all its activities

- promoting the value of human rights and equality within its supply chain

- working with responsible suppliers to understand their supply chains and products including seeking assurance of the sustainability, environmental performance and ethical standards on initial contact and in tenders

- working more effectively with local, smaller and more diverse suppliers to ensure that such businesses are not excluded from bidding for YPO business.

Knowing what we know about Amazon, it is difficult to see how it would have met these criteria, but as the VEAT declared, there appeared to be no other viable option for the contract. The framework agreement itself refers to social value stating a commitment to non-discrimination under the terms of equality law and also states:

“The supplier shall, and at all times, be responsible for and take all such precautions as are necessary to protect the health and safety of all employees, volunteers, service users, and any other persons involved in, or receiving goods from, the Call-Off Contract and shall comply with the requirements of the Health and Safety Act 1974 and any other Act or Regulation relating to the health and safety of persons and any amendment or re-enactment thereof.”

And:

“YPO will alert the Supplier by email or through their account manager of any Goods that do not meet Good Industry Practice or where YPO suspects infringement of any of its Selling Policies and Seller Code of Conduct provisions in relation to child labour, involuntary labour, human trafficking, slavery, working environment health and safety, wages and benefits, working hours, anti-discrimination, fair treatment of workers, immigration compliance, freedom of association and ethical conduct.”

There are some clauses referring to workers’ rights and ethical behaviour, but whether these could allow for the raising of concerns in a broader sense and not just specific to the delivery of the contract is questionable. Nor is it clear, given the vast array of suppliers and products, how anyone ordering through an Amazon Business framework could prove exactly where their goods had come from or whether there had been any infringement of worker rights or ethical conduct in the process.

The Framework agreement between the YPO and Amazon states clearly that it is a non-exclusive contract – so authorities do not have to purchase through the digital marketplace. But as is the case with many consumers, it feels increasingly difficult to avoid them and as the data on spending set out below shows, local authorities are spending through the Amazon marketplace for day to day goods.

Spending at local authority level

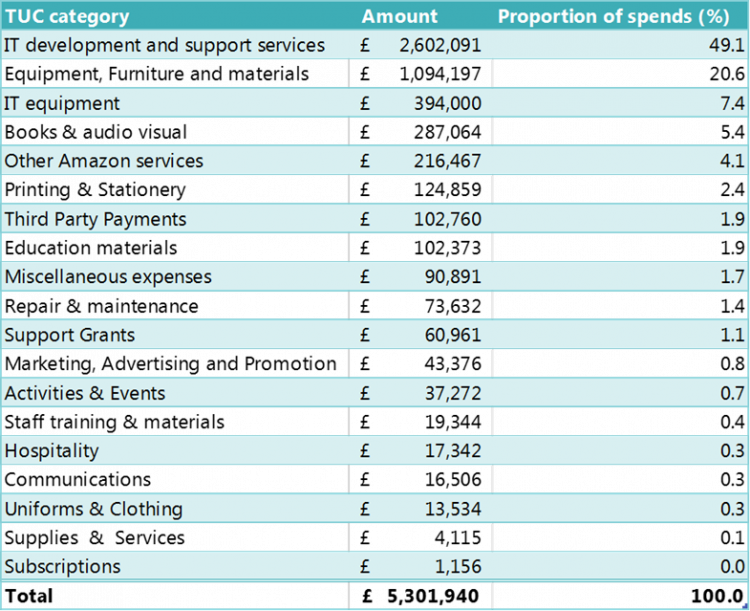

Local authorities are required by law to publish any expenditure above £500, this can be done monthly, or quarterly. Local authorities can publish spending below the £500 threshold, but they do not have to. The research we commissioned with GMB returned 52,000 individual spends between 2017 and early 2020 across 70 different local authorities at a value of £5.5 million, though most of the spending was driven by 7 local authorities.

The value is low in comparison to the large contracts from central government and the large contract from the YPO, but it does demonstrate the type of products and services local authorities are purchasing, mostly through the through the marketplace**, and as we noted local authorities are not obliged to publish transactions with a value of less than £500, so the total figure may not fully capture all purchases or the extent of spending through Amazon.

Spending on AWS related software and support has grown significantly between 2017 and 2019 – local authorities were only spending around £22,000 in 2017, by 2019 that had risen to just under £900,000.

More than half (56.5 per cent) of spending with Amazon is for the purchase of IT equipment and development and support services, and just over a fifth of spending is for equipment, furniture and materials (covering all equipment purchases excluding IT and including things like catering equipment, office furniture and equipment, tools for maintenance, mobile phones). Some 10 per cent of spending goes on books, audio visual, stationery, printing and educational materials.

As is the case with many consumers, Amazon is the first place people often look when they want to buy something online. Local governments may increasingly reflect general trends towards using the ‘Everything Store’ because of its convenience and perceived competitive pricing (YPO noted on announcing the contract, 80 per cent of their customers already used Amazon and the aim was to reduce fragmentation of spending and deliver a ‘one stop shop’ proposition).[1]

But as we raised in chapter two – Amazon is known for its unscrupulous practices in the marketplace. Reports of bullying third party sellers, using anti-competitive tactics to dominate the market, not having any clear strategy for policing the quality of what is being sold on its platform are common, nor is it clear that they really are delivering the best prices for customers.

In the US, where Amazon has been awarded a contract through U.S. Communities, an organisation that negotiates joint purchasing agreements for its members, many of which are local governments, one report from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR) suggests that local authorities could be paying 10-12 per cent more by buying through Amazon, rather than through local suppliers.[2] While the US obviously has a different system to the UK, the evidence increasingly suggests that the assumption that Amazon is the best on price is not necessarily true.

The ISLR report also indicated that as well as failing on price, the way in which the contract was proposed favoured Amazon, hobbling the ability of others to compete for the contract and by awarding to Amazon created a situation where others will increasingly have to go through the Amazon platform as third party sellers in order to reach government buyers.

The Institute for Local Self-Reliance argue:

“The contract lacks standard safeguards to protect public dollars, and puts cities, counties, and schools at risk of spending more and getting less.

The contract also poses a broader threat. Amazon is using the contract to position itself as the gatekeeper between local businesses and local governments. As it does so, it’s undermining competition and fortifying its position as the dominant platform for online commerce.”[3]

As the YPO contract demonstrates, this is clearly not just a problem in the United States. One report commenting on the YPO-Amazon Business announcement highlighted the risk that it could disrupt the market and put pressure on sellers wishing to engage with public sector buyers to go through Amazon’s seller programme[4]. Similarly, a representative from the British Healthcare Trades Association, regarding the contract stated:

“This development indicates the potential direction of travel for more aspects of public sector procurement. In the meantime, businesses may see this as an opportunity for them to supply or purchase products in a convenient way, but it may also be a threat to other models of procurement.”[5]

Amazon’s legal team had a significant hand in writing the terms of the US communities’ contract and included restrictions on Freedom of Information requests which compromise public transparency. While we have had full cooperation with our requests to local authorities here in the UK, there was some information that was restricted by Amazon as the data controller or under the terms of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 because it was deemed commercially sensitive. And in the YPO Framework Agreement it states that the YPO will notify the supplier (Amazon) as soon as practicable, or within three working days upon receipt of any requests for information under the Freedom of Information Act. Details of the request must also be shared and before any information is disclosed, the supplier should be allowed to representations regarding the disclosure and must be considered.

What does all this mean?

Much of Amazon’s activity in the UK is of course unrelated to local and central government. But as bodies that should have a key interest in promoting decent employment rights, we have chosen to focus on their direct interactions with Amazon to investigate the extent to which this might be a lever for change.

The information we have been able to gather suggests that Amazon is growing as a supplier to central and local government, but that while there is some engagement on jobs, engagement on rights is patchy. Given the many challenges that Amazon’s business model poses to decent work in the UK, the next section examines what more government could do to address these concerns.