We need major reforms to end the employment pensions lottery

Working people’s ability to access a pension has improved enormously in recent years. As many as eight million more workers have been enrolled into a workplace pension scheme with employer contributions since automatic enrolment started to be rolled out in 2012. The provision of pensions (with an employer contribution), which dwindled to a minority of private sector workers, is now commonplace.

Yet around 8.8 million workers, around one in three employees, are not currently saving into a pension scheme, according to the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE). And this headline figure, while worrying in itself, disguises great inequalities in the UK workforce.

In some occupations up to 85 per cent of the lowest paid are not in a pension scheme, and are missing out on the employer contributions that better paid workers receive. Some industries, such as agriculture and wholesale and retail, also lag far behind the norm.

Workers want money in their pockets today from decent wages. But they also want security in old age. Households in receipt of private pensions enjoy 1.6 times the disposable income of those without. Those excluded are at great risk of a low standard of living in retirement.

TUC analysis, based on ASHE data, shows:

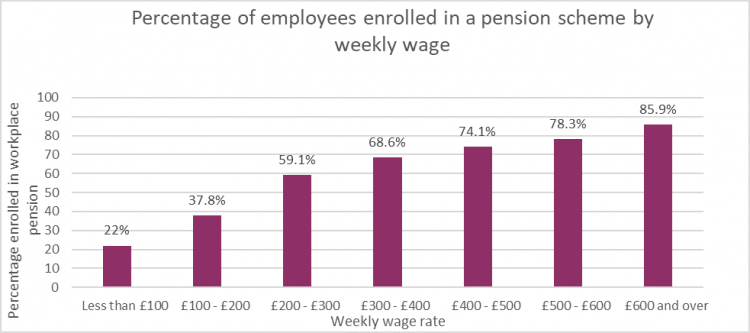

- Among highly-paid professionals earning more than £600 a week, nearly nine out of ten are saving into a pension.

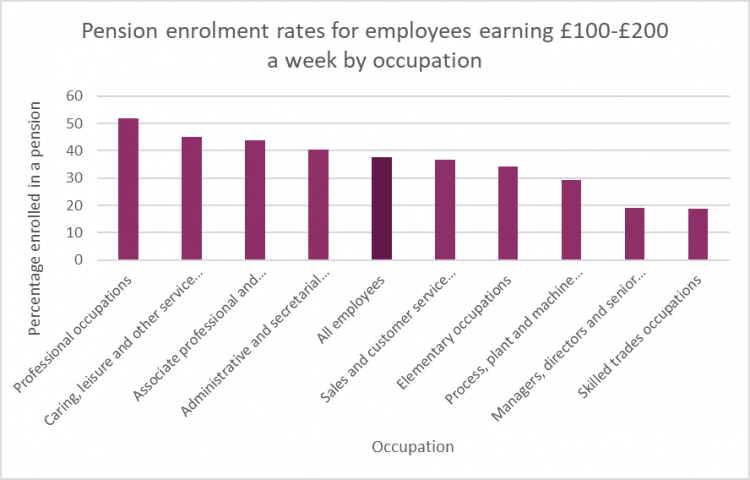

- But, at the other end of the spectrum, 85.8 per cent of those in sales or customer service jobs paying £100 or less a week are not members of a scheme.

- Four in ten employees undertaking care, leisure and other service work (39.3 per cent) are not enrolled in a pension scheme, including nearly three quarters of the lowest paid (73.4 per cent). While this is an improvement on 2012, when nearly two-thirds (62.9 per cent) of workers in this occupational group were unpensioned, it is still a sizeable gap.

- Similarly, more than half of those classed as working in elementary trades are unpensioned, including one in five of those reporting incomes of more than £600 a week.

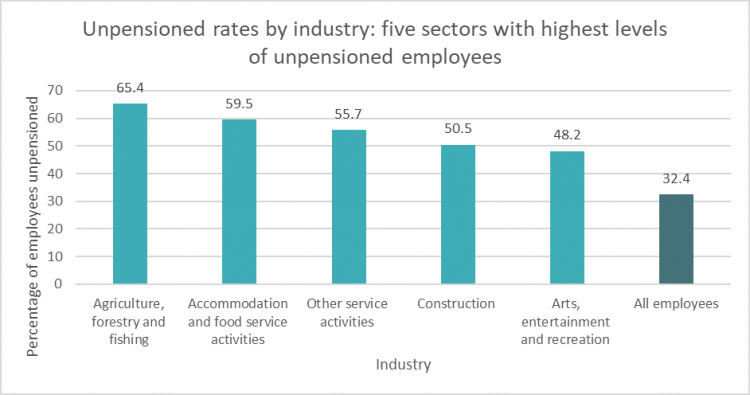

- On an industry basis, agriculture performs worst, with two-thirds of workers in this sector without a pension.

- But in absolute numbers the wholesale and retail sector ranks at the bottom with nearly 1.9 million employees, some 44.7 per cent of those working in the industry, unpensioned.

- Meanwhile, the amount employers contribute to their workers’ pensions varies dramatically from sector to sector.

This suggests that the pensions system as it is currently structured risks leaving behind millions of workers.

Our current pension set-up hardwires in inequality between low paid and better paid occupations. Those who earn under £10,000 do not have to be automatically enrolled into a workplace pension.

Many employers choose to enrol their entire workforce in a scheme. However, in other sectors, notably those without a recent history of making retirement provision for workers, firms are doing the minimum needed to comply with the law.

TUC analysis published in summer 2016 found that of the 26.4 million employees in the UK, 4.6 million (or 17.6 per cent) earn less than the £10,000 trigger level. A majority of these workers are women. The trigger has a particularly unfair impact on those 106,000 workers, (70 per cent of them women) who hold multiple jobs which combined would take them over the £10,000 threshold.

The lack of pension provision means that the pay gap is wider than at first apparent with low paid workers missing out on employer pension contributions. It also suggests that whatever gap in pay workers experience in their working lives could be amplified in retirement.

We therefore end up with industries that are pension blackspots. At the top of list is agriculture where nearly two-thirds of employees are without a pension. This includes more than 95 per cent of those earning less than £100 a week.

Other outliers include the large accommodation and food services sector where 900,000 people were unpensioned according to the latest figures, construction and arts, entertainment and recreation.

But in absolute numbers the wholesale and retail sector ranks at the bottom with nearly 1.9 million employees, some 44.7 per cent of those working in the industry, without pension provision.

Contrast this with those working in public administration, 93 per cent of whom are enrolled in a pension scheme. Or the financial and insurance sector, where only 13 per cent of employees are unpensioned.

In some of these sectors enrolment rates will have risen as automatic enrolment is extended to the smallest companies and members are captured in official data. However, it still reveals a worrying disparity between sectors.

Many of these underpensioned sectors typically employ large numbers of women. Previous TUC analysis has shown that women are less likely than men to be brought into a workplace pension scheme due to the rules governing automatic enrolment.

It is also clear that there is not a straightforward link between earnings and pension, with some occupations much better provided for, even when earnings are low. In sales and customer service roles, 85.8 per cent of those receiving less than £100 a week are not in a pension scheme. But when it comes to professionals, two in five in the same income bracket are having money put aside for their retirement.

Likewise, four out of five employees earning between £100 and £200 a week who are categorised as managers and directors, and a similar proportion in skilled trades are not in a pension scheme. But 45 per cent of those in caring, leisure and other service occupations are enrolled.

Meanwhile, 35.8 per cent of those in administration roles earning £200 to £300 a week are unpensioned, but 62.2 per cent of those in skilled trades are not saving.

The gaps in pension provision moderate among higher earners, those taking home more than £600 a week. However, professionals continue to outstrip the others, with nine out of ten of them enrolled in a pension. Occupations such as process, plant and machine operatives (enrolment rate of 80 per cent) lag behind.

This is evidence of differences in norms of pension provision between occupations and industries, particularly when it comes to the low paid. This suggests that further policy initiatives are required.

Contribution rates

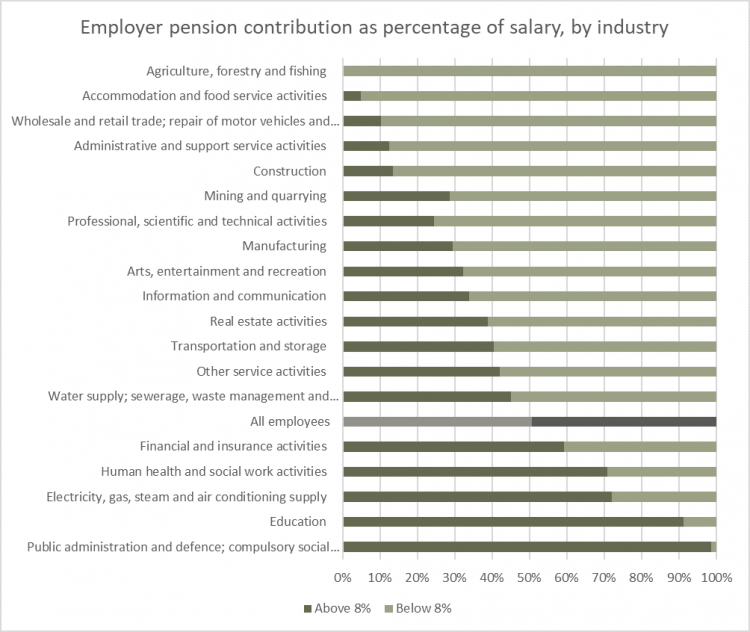

It is not just whether an employer pays into a pension that matters, but also how much they pay. Our analysis shows that this also varies widely by sector.

The amount that an employer pays into a pension is a key determinant of whether the sums saved by a worker by retirement is sufficient for a decent standard of living.

Average contributions to workplace pensions are tumbling. This shift is attributed to some extent to those employers being required to offer pension schemes for the first time, providing contributions at the legal minimum of just one per cent.

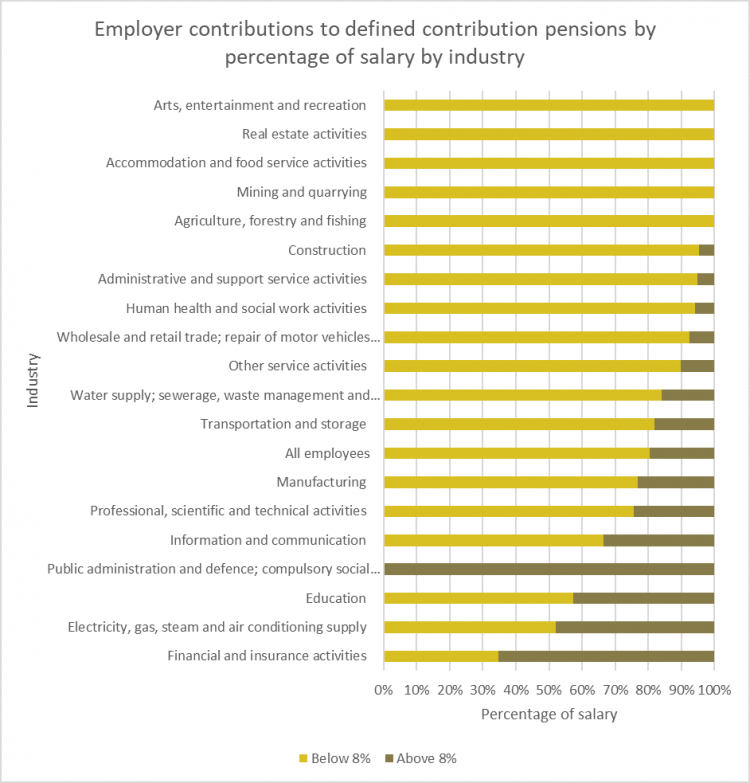

More than half of those enrolled in defined contribution schemes are receiving employer contributions of less than four per cent, according to official data. TUC analysis of ONS data shows that this includes some 88.4 per cent of pension scheme members in accommodation and food services and three quarters of those in administrative or support service activities. But only 15.2 per cent of those in financial services have such low employer contributions.

Some of the diversity is down to a division between those sectors in which defined benefit schemes are commonplace, and those where they are not. When many employers closed defined benefit (DB) schemes they took the opportunity to slash the amount they contributed to workers’ pensions. Meanwhile, regulatory pressure and rock-bottom gilt rates, which make funding schemes more expensive, mean that sponsors of many DB schemes are putting in growing amounts.

Nearly three quarters of those in administrative or support service activities receive less than four per cent in pension contributions from their employer. This contrasts with 15.2 per cent of those in financial services. Yet, more than one in five financial services workers receive employer pension contributions of more than 15 per cent. This is not a feature of a bias towards DB provision. Nearly two-thirds (64.9 per cent) of workers in this sector in defined contribution schemes receive employer contributions in excess of eight per cent.

It is evident that in many sectors low employer contributions to DC pensions are ubiquitous. Reasonable contribution rates are found largely in those industries with a history of high quality DB provision (and a relatively large trade union presence). This includes the electricity and gas sector and manufacturing sectors.

Again, there is a structural problem with the pensions system that hinders contribution rates. For a start, legal minimum contributions are rock-bottom, at just one per cent each for employers (and employees). It will not be until 2019 that total contributions will reach eight per cent. This will be made up of three per cent from the employer, four per cent from the employee and one per cent from the government in the form of tax relief.

This situation is exacerbated by the decision to apply contributions to a band of earnings, rather than base them on a full salary. For 2017/18 the band of earnings was between £5,876 and £45,000.

So for someone on £10,000 a year, only £4,124 of their earnings are pensionable, and for them, 8 per cent of qualifying earnings actually means just 3.3% of their total salary is being contributed. The rate for a median earner on £27,000 will be just 6.3 per cent. This is far short of 8 per cent and way adrift of the sorts of rates needed to have a decent standard of living in retirement.

Insecure work

Finally, what about those not captured in these figures because they work for themselves?

Since 2001, self-employment has increased by 32 per cent to over 4.5 million. Yet the number of self-employed people paying into a pension has more than halved, falling from 1.1million in 2001/02 to just 450,000 people in 2013/14. And falling numbers have savings accrued from previous jobs. After taking into account other savings, there is still clear evidence that the self-employed have lower financial wealth than employees.

This suggests that there is a major policy challenge in helping the self-employed, particularly those on low earnings save for employment. The data above on employees also suggests that where self-employment is common, in sectors like construction or the arts, or occupations such as skilled work, pension provision even for employees is lower than elsewhere. There is therefore a case for seeking to change the wider savings culture.

Major reforms are required to end the employment pensions lottery that sees some workers adequately provided for while others face a difficult old age. We need to ensure that employees have a fair and equal opportunity to build sufficient savings for a comfortably retirement.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox