The retirement lottery: what does a good pension system look like?

This means, in practice, having access to a workplace pensions system with good contributions, that doesn’t force individuals to bear by themselves the risk of investments going wrong, and is underpinned by a decent state pension.

Thanks to a mixture of deliberate policy design and accident, for most savers our current system is far removed from that.

As we have shown in a succession of blogs over the last few weeks, whether someone has a decent standard of living in retirement is to a large extent down to luck.

- Whether someone is enrolled in a pension and the level of contributions made on their behalf varies dramatically depending on the job they do.

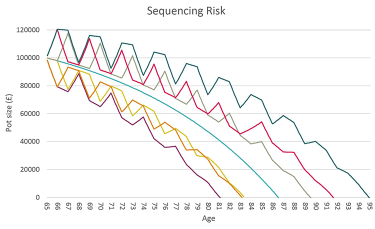

- For a member of a defined contribution scheme (the majority of today’s pension savers), where the pay-out is based on investment returns, retiring in a lucky year can add upwards of £5,000 to their annual pension compared to unluckier peers.

- We have also shown that pension “freedom and choice” reforms risk shackling savers to a retirement of uncertainty.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Looking overseas shows that other approaches are possible. We cannot import entire pension systems from overseas. But we can consider what attributes effective systems share and work towards them in the UK.

What can we learn from overseas?

The Melbourne Mercer Global Pension Index ranks the retirement systems of countries around the world on their adequacy, sustainability and integrity. The authoritative survey ranks the UK 15th out of 30 – sandwiched between Colombia and France – with a C+ grade and a score of 61.4 out of 100. Denmark tops the latest list (although it lost its A grade this year) followed by the Netherlands and Australia. Norway, Finland and Sweden also all score above 70. So what features to these systems generally share?

Good state pensions. The highest ranked retirement systems have state pensions that are much more generous on average than the UK. For people on low earnings, the net replacement rate (retirement income from the state pension and mandatory schemes as a percentage of pre-retirement income, after taxes) in 2014 was over 100 per cent in the Netherlands and Denmark, and almost 90 per cent in Australia, according to the OECD. In the UK the figure is just over 50 per cent. Those on average earnings in the Netherlands have a replacement rate of around 95 per cent, while in Denmark and Australia the figures are 66 per cent and 58 per cent. The UK the rate is just 29 per cent.

Decent contribution rates. The amount paid into funded pension arrangements – particularly by employers – tends to be much higher than in the UK. In the Netherlands contributions are generally around 20 per cent, with two thirds of that coming from employers. Compulsory employer contributions are 9.5 percent in Australia, and are set to rise to 12 per cent. Legal minimum contributions in the UK are set to rise to 8 per cent of band earnings (with 3 per cent coming from the employer), which works out at just 6.3 per cent for an average earner.

Scale. These countries typically have a small number of large schemes. While in the UK we have tens of thousands of schemes, in the Netherlands there are just 265 (and the number is shrinking – down from 422 five years ago – as the regulator nudges schemes with high costs to merge). In Australia there are around 500 superannuation funds. This means pension funds from these countries are generally very large and can use this scale to benefit their members. Even the biggest funds in the UK, with around $60bn in assets, are outside the global top 50. By contrast Dutch schemes ABP and PFZW have approximately $400bn and $200bn in assets while the Norwegian Government Pension Fund has almost $900bn.

Longevity protection/risk sharing. Most systems have an element of compulsory longevity risk protection that is missing from UK DC schemes. This means that savers cannot run out of money by living longer than they expected. Sector-wide collective DC schemes in the Netherlands, for example, provide a retirement income based on average earnings, but only give annual increases in line with inflation if the scheme is sufficiently well funded. The earnings-based element of the Danish state pension also offers conditional indexation: pensions increase in line with prices only if the scheme has sufficient funds. In this case, 80 per cent of contributions are used to buy deferred annuities while 20 per cent is invested in high return assets and used to fund annual increases.

High levels of coverage. The vast majority of workers in these countries save into a pension scheme, often because this is compulsory. In Australia employers must enrol all employees into a scheme (without the opt out available to UK workers). In the Netherlands sector wide pension funds are generally mandatory, with employers only able to opt out if they offer more generous arrangements. More than 80% of scheme members belong to this kind of scheme.

Looking at pensions in the UK, we know that radical change is possible. The Pensions Commission showed that by building the evidence base and consensus support to usher in a new system of workplace pension saving with compulsory pension contributions under automatic enrolment. The creation of state-backed provider NEST ensured that all workers would have access to a pension scheme. The imposition of minimum standards minimised some of the most egregious examples of rip-off behaviour.

These advances need to be defended, but also extended.

In our next, and final blog in this series, we will advocate a series of steps that can be taken over the long and short term to deliver an effective pensions system.

Co-author Tim Sharp

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox