Pensions: the retirement lottery

Recent reforms have led to a slew of savers cashing in their pension or using potentially risky retirement products to manage their income in retirement. This leaves them vulnerable to the corrosive impact of inflation, sharp drops in investment returns (particularly in the early years of retirement) and, counter-intuitively, the hazard of living longer than they expected.

Previously in this series of blogs we have shown that there are lottery elements to pension accumulation. Being enrolled in a workplace scheme and the amount contributed to your pension varies enormously depending on your job and industry. Likewise, variability in investment returns for many savers mean that the day someone retires could have enormous consequences for their future wealth.

But the policy of ‘pensions freedom’ is increasingly importing instability and the vagaries of luck into people’s retirement years.

For many years, workplace pensions were provided through defined benefit pensions. Incomes were paid out based on length of service and salary. Often surviving spouses received benefits, too.

The increasing use of defined contribution (DC) pensions for workplace saving requires members to find a way of generating a replacement income in retirement.

Until 2015, most DC savers were effectively compelled to buy an annuity, a contract that paid a regular income until death. But many got a poor deal by sticking with their existing pension provider. Initiatives to encourage savers to shop around largely failed.

On top of this, low interest rates adopted to cope with the Global Financial Crisis, combined with rising longevity, forced up annuity prices.

But the so-called pension freedom reforms unexpectedly unveiled in the 2014 Budget blew up the old system without putting a new one in its place. From age 55 savers could take their money out of a DC pension scheme and do what they wanted with it.

No structures were put in place to help savers navigate their options. Auto-enrolment was a policy based on the lesson that complexity, disparities of information and behavioural biases mean that savers struggle to make good decisions and providers are not subject to competitive pressure. Part of the answer was ensuring that savers were enrolled in default options subject to minimum standards and governance when building up a retirement pot. But the pensions freedom reforms assumed that no such defaults were needed in the next phase – and the market would provide.

There were no requirements regarding governance of at-retirement products. So there are no trustees making sure members get a good deal.

Nor did it put in place requirements about pricing or quality.

All that was provided was the prospect of a Pension Wise guidance appointment, which few have taken up.

Two years in, and there are many reasons for concern, set out neatly in a recent report from the financial regulator:

- There is evidence that cashing-in at least part of a pension long before retirement is becoming a cultural norm.

- Complex, opaque charges are being levied on drawdown products used by increasing numbers of savers to access their pensions savings.

- There is little evidence of savers “shopping around” for retirement products.

- There is an absence of innovation by product providers that will enable consumers to protect themselves against outliving their savings.

There is also a worrying sign that some in good quality defined benefit schemes are being tempted to transfer out into DC schemes so they can then cash in their savings. This could leave them at risk of a poor standard of living in years to come if their money runs out, falls in value or, worst of all, is lost in a scam. A recent study by the financial regulator found evidence that less than half of transfers were suitable.

Cash and corrosion

Over one million defined contribution pension pots have been accessed since the pension freedom reforms.

Around half of savers have decided to fully withdraw their pension savings as a cash lump sum.

Yet most market observers are expecting cash will yield a negative real return over the next few years.

And things don’t look much better over the longer term. The economics group at asset manager Schroders predicts a real return of 0.01 per cent a year between now and 2046.

The Barclays Equity Gilt Study 2016 shows that the stock market has outperformed cash in 75pc of all the five-year periods since 1900, rising to 91pc of the 10-year periods.

Inflation has been particularly low in recent years. But it has ticked up in recent months. A sustained pick-up in prices could see people’s savings significantly eroded.

A number of those cashing in their DC pensions appear to have (often inflation-linked) defined benefit pensions to fall back on. So they are cushioned from the impact of the falling real value of any DC pension pot they have stuck in a bank account.

But within the next few years, growing numbers of savers will rely entirely on DC pension pots. If they cash in at retirement (or even earlier from age 55), instead of generating an income or investing the money elsewhere, the consequences for their future prosperity could be very serious.

Investment dangers

Since the government removed the obligation on retirees to buy an annuity most people will remain exposed to this investment risk well into old age.

In the second quarter of 2017 just 13,800 annuities (which guarantee an income for life) were bought in the UK while 42,700 drawdown plans (which leave money invested in financial markets and let people take out a proportion each year) were opened. So just one in four DC retirees opted for the guaranteed income.

These drawdown products have their attractions. For instance, by keeping savers invested for longer, they give them the chance to build up a bigger pot and ward off inflation. But they are also riskier.

An asset manager might not make the expected returns, meaning retirement cash will run out sooner than expected. And even if the investments do perform as anticipated overall, pensioners still face a lottery if markets fluctuate from year to year. This is because the sequence of returns can have just as great an impact as the average level.

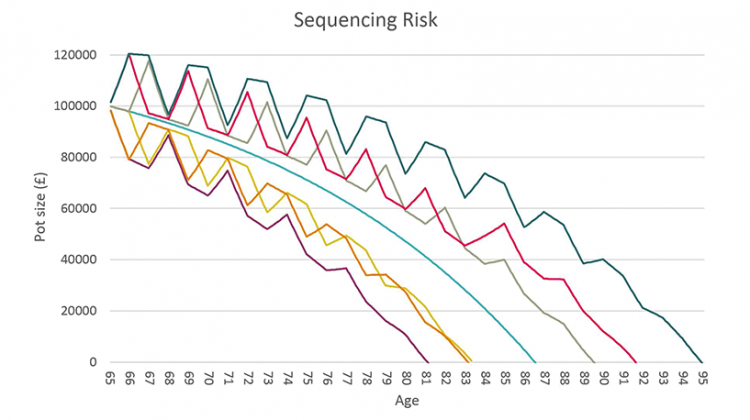

This effect – known as sequencing risk – can be seen in the graph below. It shows the age at which a retiree’s £100,000 pot of cash will run out in a variety of scenarios.

In each scenario they draw down £750 a month and their investments achieve an average 7 per cent annual growth. The figures are illustrative and reflective of the approach employed by a key academic paper on the issue, but are probably higher drawdown rates and investment returns than many would seek. However, the outcome illustrates the risks involved.

The central, turquoise line shows what happens when this return is achieved smoothly, at 7 per cent each year. The money runs out around age 86.

But if the returns are achieved on a three-year cycle of one good year (+27%) one average year (7%) and one poor year (-13%) this varies significantly. The various combinations of these circumstances are also shown below.

In the worst scenario, the fund starts in a poor year, followed by an average year. The effect of future growth being generated from a smaller pot, plus the regular withdrawals, is that the stellar performance in year three still doesn’t take the fund back to the ‘average’ level. As this is compounded over time, the fund runs dry five years earlier.

On the other hand, if the high returns come in year one of the cycle, the fund could last until age 95. So even in this simplified model, the same size fund, achieving the same average returns, with the same level of drawdown, could last anything from 16 to 30 years.

Living too long

Even if a saver could predict when a pot in drawdown would run out, this would not be particularly useful unless it was combined with an equally accurate prediction of how long they would live.

Research from Aviva has found 65-year-old men underestimate their life expectancy by 3.3 years on average.

But even if we were all a bit less pessimistic about our probable lifespan, in a system where the individual is responsible for managing their own longevity risk there is still a great deal of uncertainty.

As the Pensions Institute’s Independent Review of Retirement Income points out: “Being told their life expectancy is a completely useless piece of information for someone who has just retired, since there is an approximately 50 per cent chance that a 65-year old man, for example, will live beyond his life expectancy of 86.7.”

And around one in four will live to at least 93. Even at higher ages, the average life expectancy of an 85-year old man is 91.6 but one in three will reach 93 and one in twenty will live to 100.

Defined benefit schemes and insurance companies that sell annuities manage this challenge by pooling large numbers of people together. Those unfortunate people who die earlier than expected cross subsidise those who have an unexpectedly long life.

This means that every individual only has to save enough to last them the average lifespan. Without access to this pooling they are faced with a choice of significantly oversaving, or accepting a 50/50 chance that their money will run out while they still need it.

Conclusion

In granting savers “pensions freedom”, there is growing evidence that retirees have had other freedoms taken away such freedom from making bewildering and complex choices and freedom from worry through retirement.

The potential negative consequences of these policy choices have been limited so far. Many retirees have secure DB pensions to fall back on. Meanwhile inflation has been relatively low and investment market returns have been high.

But this won’t last forever. We need reforms today to bring increased stability into the retirement regime.

Co-authored by Tim Sharp

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox