A new economic way is possible in 2018 – but history tells us we need policy change

2017 saw the seventh year of falling real wages of the nine since the financial crisis, the eighth straight year of (per head) public service cuts, and the weakest GDP growth for five years.

What’s more, in 2017 many policy makers seemed to give up on their earlier optimism that a recovery was just around the corner. The Office for Budget Responsibility argued that productivity – a measure of the efficiency of the economy and regarded as critical to the strength of GDP – was unlikely to recover to the levels seen before the financial crisis in the foreseeable future.

The Bank of England raised interest rates, not because it viewed economic growth as too swift, but because it likewise believes that the capacity of the economy has fundamentally weakened, so that even mediocre growth could generate inflation. And without faster growth to repair the public finances, austerity is reckoned to continue pretty much indefinitely.

In effect, policymakers have given up on the idea of repairing the economy. Doubtless they are right that the future is dismal on the present course. But they continue to ignore the possibility – likelihood – that policy is responsible. A look at the lessons of history suggests a different way is possible – but only with a change of course on fiscal policy.

After a brief recap of these changed judgements this post contrasts the failed implementation of austerity policies of the past decade with the successful rejection of austerity policies after the great depression.

1. Policymakers change their minds

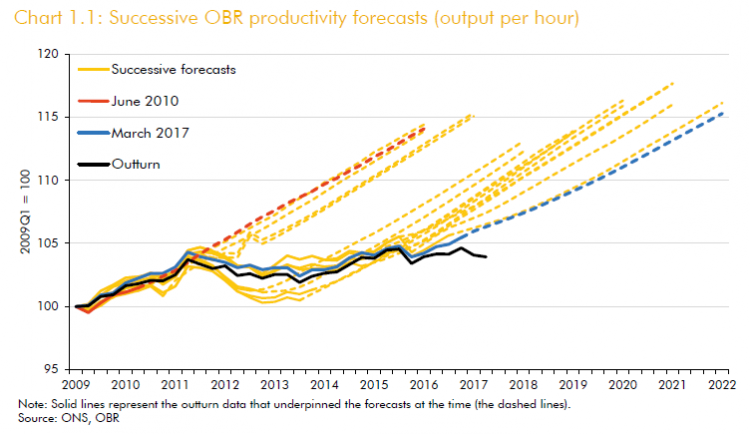

The first sign that policy makers were changing their minds about how swiftly the economy was likely to grow was given by the OBR in their October Forecast Evaluation Report (discussed in more detail here), and illustrated by the following chart of productivity outcomes:

The chart starts with a revival in productivity as the economy came out of recession (as a result of global stimulus), and then the revival stalling (black) rather than continuing as expected (red).

Each of the ‘successive forecasts’ (in yellow) sees the OBR expecting the revival to resume – right through to the March 2017 Budget (in blue). But it never did.

The October forecast report saw the OBR putting us on notice that they were no longer going to continue this charade, and next time they would be moving their expectation of the future more towards the reality of the past.

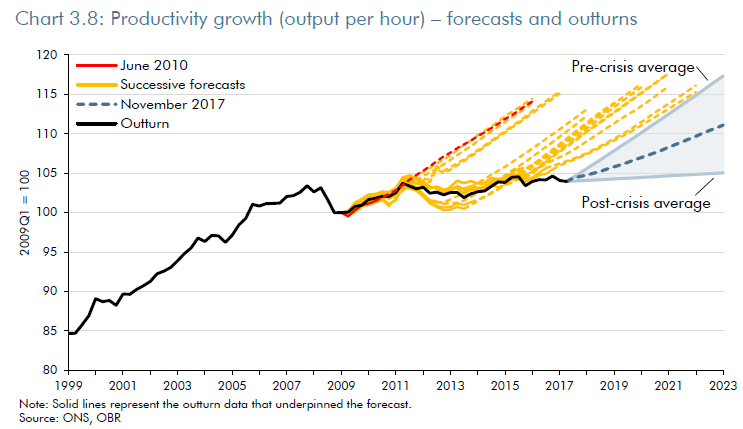

Before we found out exactly how far they were going it was the turn of the Bank of England in their November Inflation Report and policy announcements. Their own downgrade for productivity meant a downgrade for the supply potential of the economy. They argued that with supply down and demand expected to be unchanged, inflationary pressures will build, and on this basis, raised interest rates, and indicated that they would expect further hikes in the future.

At the November Budget, the OBR revealed their new estimate for productivity – confirming their earlier indications of a significant downgrade.

The sum of the parts is bleak. As our post-Budget commentary showed (see here) the OBR no longer expect real wages even to recover their pre-crisis peak, and the OBR no longer expect the public finances to be brought into balance.

Yet despite the changed judgements of forecasters about the prospect of a revival in economic growth, there is no sign of government changing its mind when it comes to macro-economic policy. Once more spending cuts were extended for another year, making 13 years in total (and expected to continue). And while investment spending was boosted (or is forecast to receive a boost in the latter years of the parliament’, investment spending will remain lower than in the last parliament, and the UK will remain at the bottom of the international league table (see our post-Budget post).

2. Could things be different? The lessons of history

The origins of the present policy of austerity go back to pessimistic judgements made in the wake of the global financial crisis. With the worst of the crisis over, policy was then based on the idea of the financial crisis indicating the economy living beyond its means. (The fact that there was no inflation – traditionally the indicator of overheating – was ignored.)

Only after retrenchment would growth be able to resume at roughly the same rate as before the crisis. Government also had to retrench, in part because of the costs of the financial bail-out, but also because previous spending plans were based on an assumption of uninterrupted growth. Conversely monetary policy would provide stimulus.

The only relevant precedent to the 2007-08 financial collapse is the implosion that preceded the great depression of the 1930s. And likewise the only meaningful precedent to the scale of the present monetary stimulus was the actions following the great depression.

But, despite the reputation of the 30s as a decade of economic mismanagement, not least excessive emphasis on protectionist policies, a very much more constructive mindset prevailed then, with very different results.

3. Monetary Policy

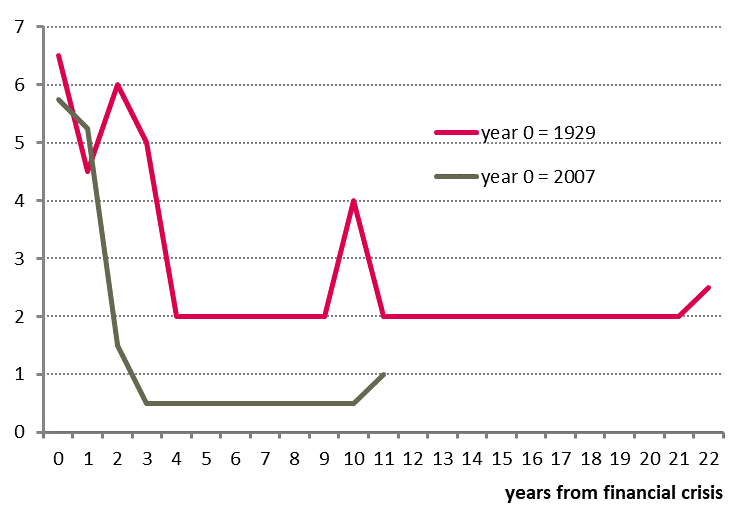

When it comes to monetary policy, the response from the Bank of England looks pretty similar in the periods following 1929 and 2007. The chart below shows an annual series for Bank rate, with the 1930s and the present shown on the same axis – both start at the peak of the pre-crisis boom according to real GDP per head (see later).

Bank rate, annual maximum

Source: Bank of England [The chart shows the highest level the rate reached in any calendar year, and so the present rate rise is seen in a (illustrative) forecast for 2018, with the maximum rate in 2017 = 0.5 which is the same as the maximum rate in 2016, even though rates were cut to 0.25% for parts of both years.]

Monetary ease followed a broadly similar path, but with certain differences:

- Bank rate action initially proceeded at about the same pace in both cases (too slow), but was held up in mid-1931 as the gold standard forced contradictory monetary policy action in the face of a global banking crisis. UK membership of the gold standard system was ended in September 1931, when monetary ease was able to resume.

- Rate cuts in the 1930s did not proceed quite as far as in the 2000s

- Rates were held low for twice as long after the great depression, outside a misguided tightening at the start of World War Two that lasted for only two months

The rate cuts in the 1930s were also part of much larger-scale monetary reform: as above the gold standard was terminated, a new system of managed exchange rates was introduced, and, with the conversion of the 5% War Loan to 3 ½%, the Treasury also began to operate directly on the long-term interest rate, alongside which capital control was implemented. Rate cuts in the 2000s are still framed in the unchanged context of the pre-crisis inflation-targeting framework, notwithstanding colossal levels of QE, large scale subsidies to the banking system and a greater flexibility with the rules of the regime (not least the 2012 ‘new framework for monetary policy’ in the UK).

4. Fiscal policy

When it comes to fiscal policy however, the approach is strikingly different. In February 2010 twenty eminent figures set the tone for the general election campaign, calling for austerity in a letter to Sunday Times. Eight years later, their advice continues to define a policy that will not even be finished by 2022-23.

In the 1930s, rather than academics and policymakers, it was the City urging fiscal restraint. In the third volume of his History of the City of London, David Kynaston (p. 233) cites a letter signed (on 30 July 1931) by nine leading City figures:

“What we have urged other nations to do, we must now do ourselves, namely, restrict our expenditure, balance our budget, and improve our basis of trade”.

But in the 1930s, the advice was soon disregarded.

By 1934 a serious expansion in government spending was underway. According to Chancellor Neville Chamberlain’s rhetorical flourish in his Budget speech: “we have now finished the story of ‘Bleak House’ and that we are sitting down this afternoon to enjoy the first chapter of ‘Great Expectations’”.

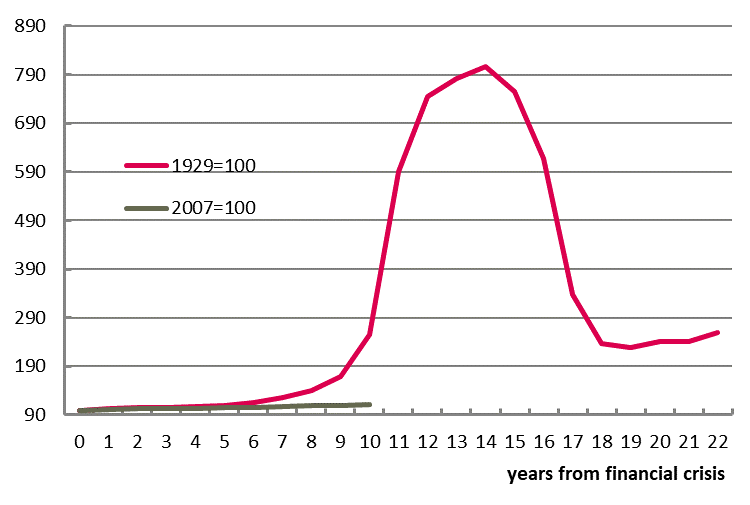

The charts below compares figures for government spending in the early years of the low interest rate policies for both the great depression and now (A), and then throughout the cheap money episodes as a whole (B).

Government final consumption expenditure, indices in real terms (A)

Government final consumption expenditure, indices in real terms (B)

Source: Bank of England historic data spreadsheet

The departure of spending in the 30s relative to now is clearly seen, with the pace of spending rapidly accelerating over 1935-37 (years 6-8). The second chart moves to mobilisation for war and then the war itself. From the fiscal point of view, policies were as different as it is possible to be. Note too that after the war government spending was retained at more than double its level at the start of the 1930s. Contrary to the advice of the bankers, the UK was able to afford expanded expenditure through a stronger economy.

5. Results

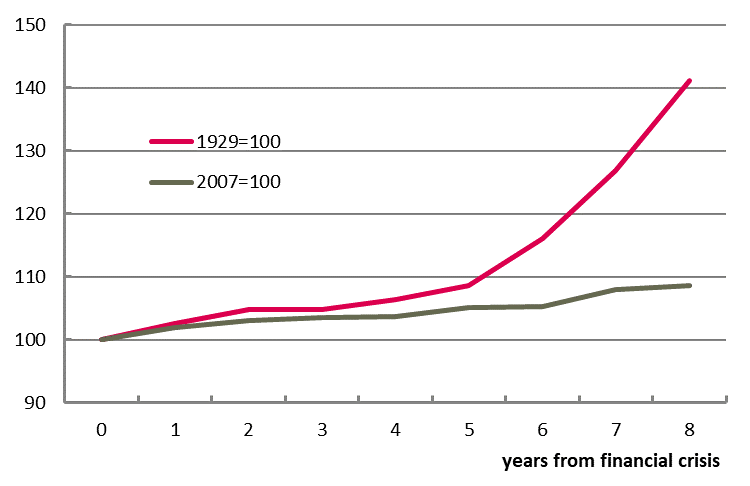

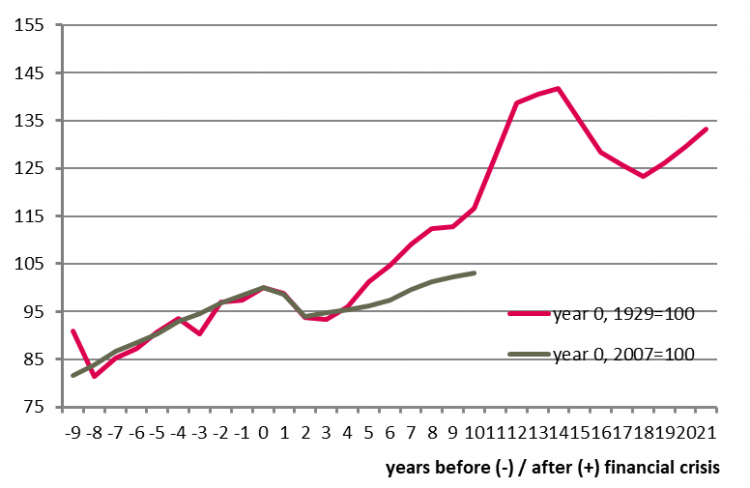

The next chart compares results on the basis of GDP per head: this chart also includes results in the run up to the respective recessions.

GDP per head, indices in real terms

The similar scale of the two recessions is striking. Perhaps the dysfunctional monetary policy response meant the 1930s downturn was worse. But from 1933 recovery really got going, with growth faster (the line is steeper) than ahead of the crisis.

The present point (2017, given the OBR forecast for Q4) corresponds to 1939 (year 10). In 1939 GDP per head was 25 per cent above the low point in 1932, with growth averaging 3.6 per cent a year from the trough; in 2017 it is up by only 10 per cent, with growth of 1.2 a year. So growth was three times as fast after the great depression than in the present ‘recovery’.

The great spending increases then further ramped up the economy for the war; after the war there was a downwards adjustment and then growth resumed apace (at almost 3 per cent a year).

Moreover, throughout the whole of this expansion, it was not deemed necessary to increase Bank rate. That came only when the Tories took office again in 1951..

6. Discussion

Fundamental to these outcomes was Keynes’s call to proceed on this basis of optimism. This was more than a whim, and was rooted in his judgement about the nature of the great depression. He considered the depression meant dysfunction, not that the country was living beyond its means. He had argued that the gold standard and wider liberalised regime imposed in the 1920s was fundamentally flawed, and repressed economic growth but made conditions more volatile. The financial crisis and great depression of 1929-1931 vindicated that judgement. He was optimistic because the failure offered the opportunity to get it right.

The Conservative administration through the 1930s and then the Labour government in the 1940s seized that opportunity.

Compared with the experience of the 1930s, the actions of policymakers today (not just in the UK but across the globe) have continued to repress activity and so also jobs and wages. Savers are hurt by excessive and ineffective reliance on ultra-low interest rates, and everybody is hurt by austerity. Hard pressed families who have had to resort to unsecured borrowing will now be hurt by rising interest rates.

This time the financial crisis was treated as a random malfunction of an apparently otherwise sound system, rather than anything more far-reaching. The living beyond means hypothesis was seemingly devised with no regard for history.

The recent judgements by the OBR and Bank of England amount to a recognition of the extent of the failure of the present policy course. But with their heads buried in the sand of productivity figures that are symptom not cause, it is the reverse of a strategy that will make anything better. There is now evidence across all OECD countries that spending cuts damaged economies far more than expected (here). Perhaps 2018 will be the year that the lessons of history are finally heeded.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox