Bank of England are raising interest rates because of imagined wages growth

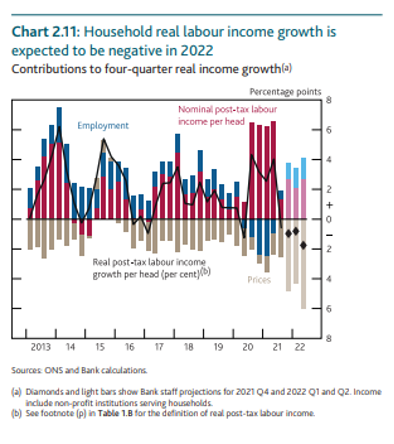

For workers the punchline is that real pay will fall by 2% this year. This then feeds through to real income contracting “even more sharply” – see the Bank chart below.

Worse, workers are warned that they will make it worse by securing decent pay rises. On the BBC the governor called for “Moderation in wage rises”, and warned of inflation becoming ‘entrenched’. In their Monetary Policy Report the Bank (p. 9) find “underlying wage growth is materially stronger than in November”.

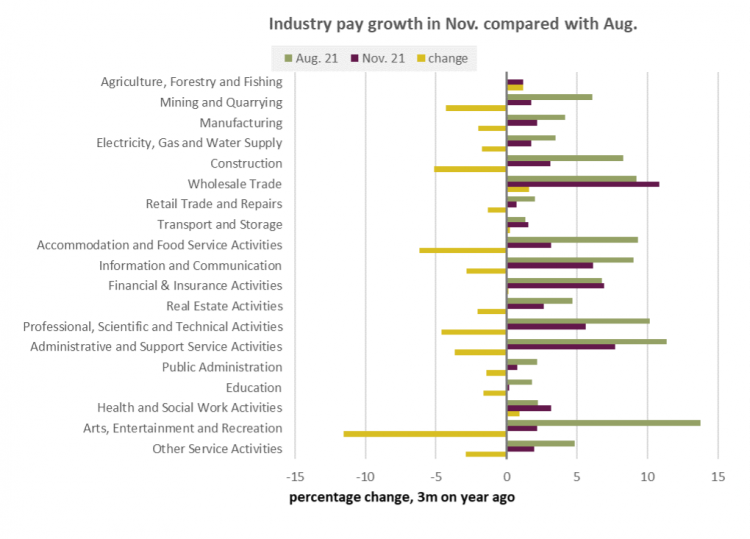

Pay is slowing not accelerating

Chance would be a fine thing. The official statistics show regular pay growth already slowing to 3.8% in November from 4.2% in October (not mentioned by the Bank). Our latest Jobs and Recovery Monitor shows an industry view with pay growth slowing across the board.

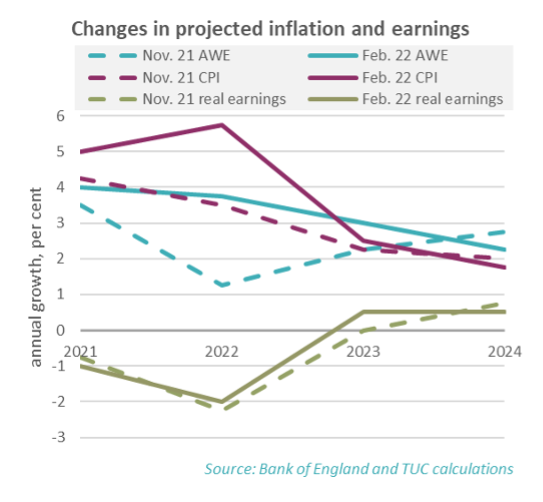

Bank forecast

In fact, the main evidence of increased pay is in the imagination of the Bank of England. What we saw last week was the Bank conceding they had underestimated inflation, so for example CPI will be 2¼% higher in 2022. They then changed their forecast for average earnings by more than the amount of the error in inflation (2½%). As the chart below this serves to keep the real wage forecast actually a little better than before.

So they are assuming that workers will be able to negotiate pay rises to match the changed position on inflation. Why they are able to make this judgement now when the actual position on wages is worse than when they made their last forecast in November depends on their own special information, some ad hoc figures and because theory tells them so.

The Bank Agents

The Bank report the finding of their ‘Agents‘ that ‘wage settlements are expected to be much higher in 2022 than in 2021’. This however rather contrasts with other sources. Our monitor reports the finding of our own polling that 2/3 of workers do not expect pay rises to keep pace with increases in the cost of living, with half of these not expecting pay to go up at all. ONS polling of businesses shows 52% of companies saying that wages have not been affected by the pandemic (and the few saying wages are higher than normal are basically offset by those saying wages are lower than normal).

Ad hoc measures

The Bank report various ad hoc measures at multi- year highs, e.g. recruitment difficulties, high rates of job change, pay for new hires etc. None of these mean good wages across the board, and the official data on wages are basically ignored.

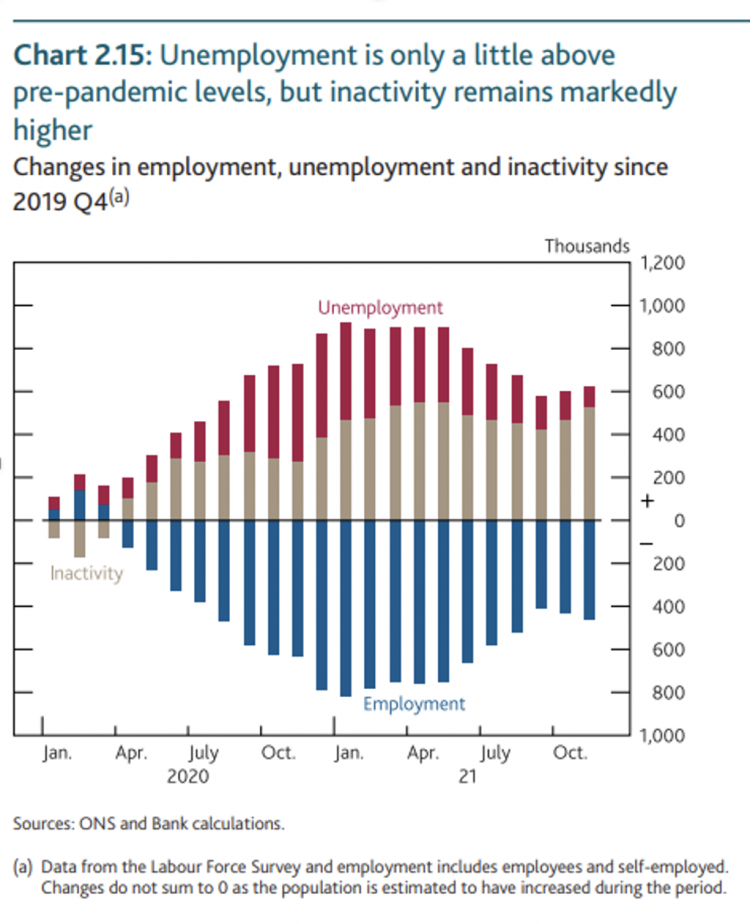

The ‘tight’ labour market

But above all they resort to ‘it happens in theory so it must happen in practice’. According to certain notions of natural rates, when unemployment falls below a certain level the jobs market is ‘tight’ and wage inflation must follow. So with unemployment now lower than before the pandemic, we have an imagined pay rise.

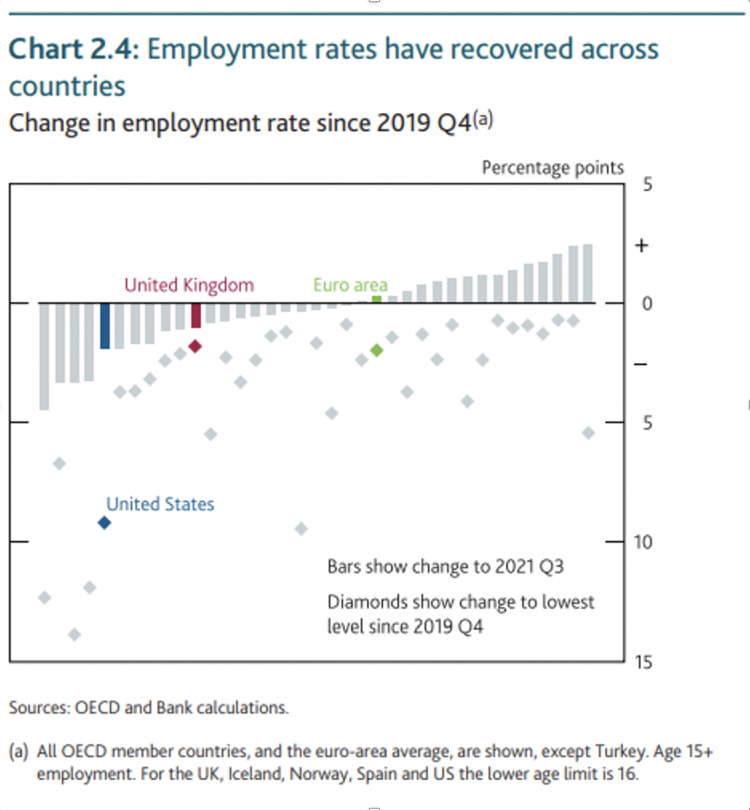

Even at face value this is contentious. The Bank themselves show how overall employment is still down nearly half a million, with those without work going into inactivity rather than unemployment (left chart below). They also show that the UK position on employment is towards the lower end of OECD countries (right chart below).

But more importantly this has been the story for more than a decade. The Bank keep appealing to low unemployment meaning high wages in the future that have never materialised. Instead we have an epidemic of insecure work and the worse pay crisis for at least two centuries.

Policy in practice and reality

So the interest rate rise is based on a judgement in theory that we should know is broken. We are told not to fight for higher wages, but the Bank are already acting as if pay is already up.

In reality, as the Bank have repeatedly argued, rate rises will do nothing to stop inflation in the international markets where it originates. In the face of a cost of living crisis it will serve only to impose further cost pressures onto businesses and households.

Rather than calling for pay restraint, the Bank must recognise that a pay rise is the best solution to a cost of living crisis.

Businesses and policymakers forget the macroeconomic point that workers are customers too, and higher pay is the only thing standing in the way of collapsing sales. And it is striking that businesses have proved reluctant to take a hit on their profits, and have always been able to find big fat dividend payments. In a discussion of the Bank’s actions on twitter the Financial Times journalist Martin Sandbu wondered:

“Genuine question: why does the governor of the Bank of England encourage restraint in wage demands but not call for restraint in businesses’ attempts to protect their profit margins? Intellectual bias, ideology, greater resignation wrt price- than wage-setting, or something else?”

But the problem goes much deeper. Workers once more find themselves in the firing line for policy failures – from austerity to the failure to address global financial imbalances, or to come to a better agreement on how to moderate energy prices. The hardship imposed on households over the past decade has contributed to a situation where people cannot cope with sudden price changes.

On a more technical level, this isn’t the first time that central banks have tried to tighten policy over this period, and already we are seeing the disarray in financial markets that each time brings any such efforts to a premature and embarrassing end. Just today the FT are reporting ‘US stocks record their worse day in almost a year as Meta plummets’.

Calling for pay restraint is the wrong solution to a misdiagnosed problem. Instead, we need action to solve the cost-of-living crisis now, and to shift us to a high pay economy:

- The pandemic has taught us the importance and power of government action to protect the economy and workers. Policymakers need to keep monetary and fiscal policy on an expansionary setting, and government spending should be aimed at decent work and tacking the climate and social care crises

- As pay rises won in a number of disputes show, a strengthened role for unions is the way to secure decent pay rises across the economy. The government needs to support union strength in workplaces across the economy and likewise extend the role for collective bargaining, including at sectoral or industry level. On top of this the minimum wage should be £10 now

- Public sector workers need treating fairly, rather than repeatedly targeted by austerity policies. Pay review bodies must lead on a changed mindset, escaping the zero-sum thinking that has caused more than a decade of stagnant real pay across both the private and public sectors.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox