Our workplaces aren’t fit for the future. What are we going to do about it?

We reckon there’s two reasons for this: rubbish jobs and a lack of investment in the existing workforce.

While the lack of investment is an important part of the explanation, poor workplace practices also play a role. Poor quality employment practices, weak enforcement of labour rights and low investment in training have left us lagging behind.

The rise of insecure work, the lack of decent support for working parents, and the UK’s failure to invest in workplace skills not only limits working people’s prospects, they hold our economy back.

Rubbish jobs

We’ll start with the rubbish jobs. Despite record employment rates, too many people still face significant insecurity at work. Not only do they often face uncertainty about their working hours, but they also miss out on rights and protections that many of us take for granted.

The increase in insecure has hit those already disadvantaged the hardest. Women, minority ethnic groups and those in poorer regions are more likely to be in insecure work.

Those in insecure work are more likely to miss out on rights and entitlements such as sick pay. They also face a significant pay penalty. It’s particularly difficult for parents, who are forced to combine insecure work with caring for their families.

There’s a risk that high levels of insecure work have become the new normal. Self-employment continues to rise, the number of temporary workers (not including fixed term contracts) remains high, as does the number of people on zero-hour contracts.

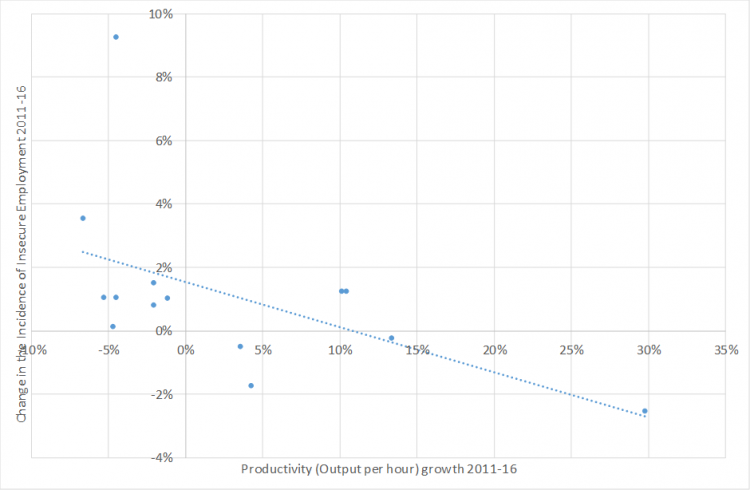

There’s evidence that Britain’s reliance on a poor-quality employment model may help to explain our poor productivity. Analysis for the TUC by the Learning and Work Institute looked at the relationship between productivity growth and insecure employment between 2011 and 2016.

It turns out productivity growth stalls when there is a higher incidence of insecure employment. Sectors with higher increases in productivity tended to experience falls, or smaller increases in insecure employment than other sectors.

There’s a reasonably strong correlation between lower productivity growth and higher increases in the incidence of insecure employment.

Productivity Growth and Change in the Incidence of Insecure Employment 2011-16

Correlation doesn’t mean causation, but it makes sense that if you have no idea when you’ll be working, or how much you’ll be paid, or whether you have access to any rights at work, you’re likely to be less productive than those in more secure employment.

Poor employment practices don’t just exist in insecure jobs. Across all jobs, poor quality employment practices have direct costs for businesses, with 15 million working days lost in 2016 due to stress, anxiety or depression.

Failing to invest

It’s not just rubbish jobs that need addressing. Under-investment in workforce skills by government and employers has long been a feature of the UK labour market. However, we now face a looming skills crisis.

A range of factors, including Brexit and rapid technological change, will accelerate the demand for skilled workers in a wide range of sectors to a much greater degree than we have witnessed in recent decades.

Without urgent action by government on this front it is highly likely that skills shortages will escalate and the long-standing productivity gap with other major economies will widen further.

The reforms to boost investment in apprenticeships and develop new technical education qualifications are welcome, but they can only be part of the solution to meeting the skills challenge. The overall picture on adult skills investment remains very weak.

A third of UK employers admit to training none of their staff. UK employers invest only half as much per employee in continuing vocational training as their EU counterparts.

Investment in training and learning per UK employee fell by 13.6 per cent per employee in real-terms between 2007 and 2015. Government spending on adult skills and further education has also been cut sharply.

What needs to be done

We need to sort out the rubbish jobs. The government should set out action to deliver great jobs for everyone.

Our Great Jobs Agenda sets out actions to expand voice at work, raise levels of pay, ensure regular hours, strengthen action to promote equality at work, improve health and safety at work and ensure everyone has the ability to learn and progress.

An important part of ensuring great jobs is making sure existing rights are being enforced.

The upcoming budget should therefore increase the resources of the enforcement agencies to make sure existing rights, including the National Minimum Wage are enforced. This must cover those in the social care sector, currently waiting for back pay for sleep-ins.

We also need investment in skills for those already in the workplace to help people manage and thrive when jobs change.

It’s estimated that two thirds of the 2030 workforce have already left full-time education and these people are most at risk of being left behind in a rapidly changing labour market. To make sure workers have the skills they need to take advantage of new opportunities in the labour market, government needs to focus on those in the workplace now as well as increasing investment in apprenticeships and new technical courses.

We’re very happy about the boosted funding for apprenticeships through the introduction of the levy and the government’s commitment to an additional £500M of funding per annum for the new T levels when they are fully up and running.

However, this in itself isn’t sufficient to deal with the potential skills crunch facing the nation as employers and employees face up to rapid technological change and the skills fallout from Brexit.

The full set of new T levels will not be available to students until autumn 2022 at the earliest and the reformed apprenticeship system will not have the capacity to generate enough skilled labour to meet demand in the economy.

In order to boost opportunities for retraining and upskilling significantly, the TUC is calling on the government to take a number of steps, including:

- Setting an ambition to increase investment in both workforce and out of work training to the EU average within the next five years

- Introducing a right to a mid-life career review and face-to-face guidance on training

- Introducing a new life-long learning account, providing the opportunity for people to learn throughout their working lives

- Introducing a new targeted retraining programme aimed at certain groups including those facing redundancy due to industrial change.

Image: Oli Scarff / Getty Images

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox