Our 150 years show that stronger unions mean a better economy

This year we’re celebrating 150 years since the first Trades Union Congress took place on 2 June 1868 at the Manchester Mechanics’ Institute.

The anniversary reminds us of the giant steps forward we’ve taken in improving working life, but also of the challenges that still lie ahead.

Our 150 years also show that the strength of the economy goes hand in hand with the strength of trade unions.

And that in the troubled economic times we live in today, the need for trade unions is greater than ever.

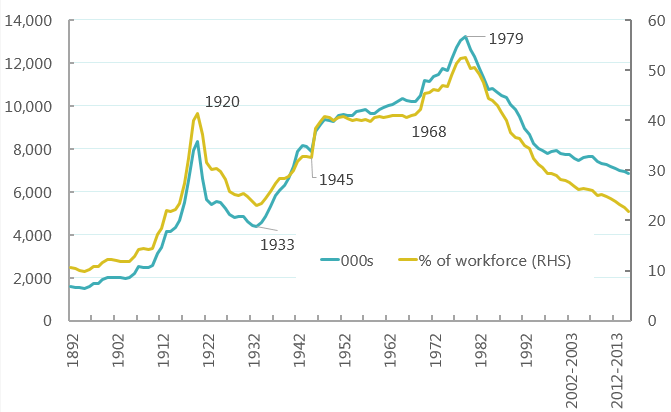

Peaks and troughs in union membership

Trade union membership has certainly ebbed and flowed over the last century and a half, as the following chart shows:

We can see that membership rose to a first peak at the end of the First World War, both by headcount and as a share of the workforce.

The figures then went into steep decline until the lowest ebb of the Great Depression in 1933, before decisive gains during both the pre and post-war period.

These gains accelerated from 1968 (following a successful 100th anniversary campaign?!) until they peaked – when else? – in 1979.

From that point, however, trade union membership has been in retreat (though the latest figures show a slight increase in 2018).

But while membership numbers are clearly at a low ebb right now, the history gives us a sense of the possibilities that could lie ahead.

Just forty years ago, over half of the workforce were members of a trade union. Today it is barely 20%.

So as we reflect on 150 years of the TUC, it’s clear we need to find a way to inspire new generations to join and sustain the movement for another century and a half.

One of the ways to do so is by reminding people that stronger unions mean a stronger economy – and that means better paid jobs for everyone.

Stronger unions, better wages

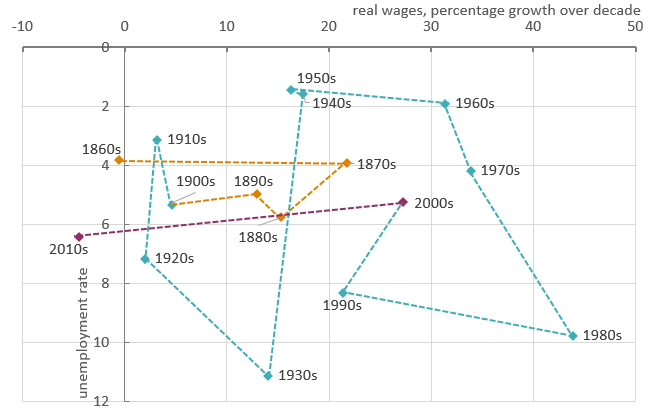

Labour market comparisons over the last century and a half show the power of strong unions.

This is demonstrated in the next chart:

Each data point shows a decade average for the unemployment rate (on the vertical axis) versus real wages growth (on the horizontal axis), connected in chronological order (orange for the 19th century, turquoise the 20th and magenta the 21st).

Note that ‘decade’ is measured to years ending in ‘8’, so that we start with the decade ahead of the first Congress (1858-1868) and end in the decade to now (2008-2018), using the OBR forecast for 2018.

So in the decade before the first TUC meeting in 1868, real wages had fallen by 0.1%. Since then, only the decade to 2018 has seen a worse performance, with real wages down by a whopping 4.4%.

While government ministers keep telling us to celebrate low unemployment, the 6.4% average unemployment rate over the present decade is actually worse that than that in the decade to 1868 (3.8%).

And while the decade of the Great Depression saw a steeper drop in the rate of unemployment, the current decade is the worst in our history for wage growth.

By contrast, the period when trade union membership was at its highest – the thirty years between 1950 and 1980 – were best for wage growth.

That’s why stronger unions mean better wages for workers.

The early years: 1868-1914

Workers’ early efforts at organisation and combination were strongly resisted by long-established vested interests.

Unfortunately, this included the economics profession, which saw no use in such efforts. David Ricardo (whose ‘Ricardian economics’ is still deployed today) offered an early taste of the dismal science (at least dismal as far as workers were concerned):

As the authors of an excellent paper on the early economic theory of trade unions put it , “the shared assumption was the notion that trade union activity, whatever else could be said about it, is in any case of no benefit”.

Yet in the three decades after the TUC first met, real wages grew by an average of 17 per cent a decade.

A world in turmoil: 1914-1939

Unfortunately, progress then went into reverse.

Promises made to those who returned home from the battlefields of the First World War were not honoured, and the disastrous and brutal economic policies of the 1920s led to immense hardship.

The General Strike in 1926 was a howl of rage against a government that tried to deflect the blame for its own policy failures on to trade unions by arguing that wages were too high.

It then upped the ante with the ‘Trades Disputes and Trade Unions Act’, which made general strikes illegal, prevented civil service unions from engaging in wider union or political activity, and enforced a contracting-in system for political fund contributions.

But these disputes sowed the seeds of future gains, as the following quote from the socialist intellectual G. D. H. Cole in the official history of the first 100 years of the TUC makes clear:

The book the explains how this impacted on the development of the TUC’s own policies:

As the last chart shows, the 1930s marked the lowest ebb in unemployment. But this was also the decade when the seeds of change began to take root. Indeed, Keynes’s work was “not without influence in the policies and expedients of the National Government itself”.

From world war to a world transformed: 1939-1979

The Second World War was a different kind of war, with the economy by this point run in the interests of labour rather than capital.

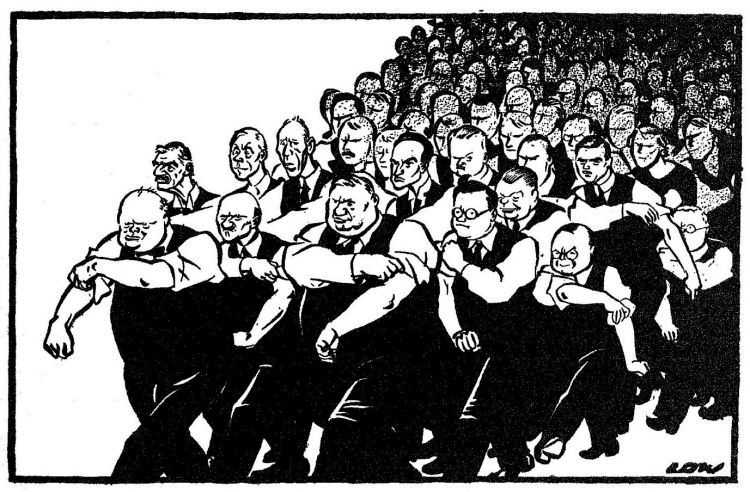

As the wonderful David Low cartoon below illustrates, it was Labour and not Conservative figures who were on the front line of the politics with Churchill – none more so than Ernest Bevin, general secretary of the TGWU and the dominant trade union leader of the time.

Despite the pressures of fighting a total war, the utmost was done to support workers by maintaining real wages at a decent level throughout the 1940s

And after the war, the courageous and revolutionary Attlee government continued to act on the lessons learned in the 1930s to ensure there was no repeat of the economic disasters that had followed the First World War.

Full employment became the explicit goal of economic policy, and unemployment was maintained below 2 per cent into the peace.

Even when the Conservative Party were re-elected in 1951 they did not (greatly) depart from the Labour model for the 1950s.

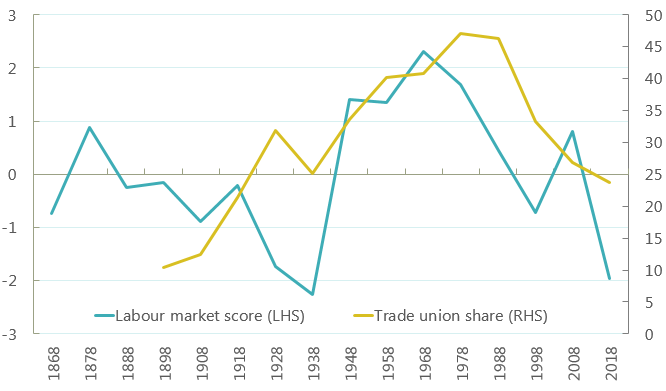

This was a period when unions had never seen stronger and more sustained membership, as the next chart will show.

The third chart below is a composite measure of labour market outcomes, combining unemployment and real wages. The figures are plotted against the trade union share by decade:

(The labour market score is derived from normalising (i.e. subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation) unemployment (inverted) and wages outcomes, and then adding the two together.)

We can see that labour market outcomes in the decade to 1968 were the best on record, but more generally outcomes over the four decades from the 1940s stand out from all others before or since.

In other words, labour market gains were never better than when unions were at their strongest.

From Thatcher to the crash: 1979-2008

When Mrs Thatcher came to power in 1979, trade unions were once more in the firing line for the deterioration of economic outcomes, not least the inflation of the 1970s.

The 1994 OECD Jobs Study articulated the new (or rather, renewed) agenda of flexibility against which unions have struggled ever since:

Yet the subsequent and partly consequent decline in trade union membership over the two decades to 1998 did not lead to any improvements in economic outcomes.

Instead, as the figures show, outcomes progressively deteriorated. And the reversal in the decade to 2008 proved short lived, as the outbreak of the global financial crisis and the imposition of austerity strangled any prospect of material recovery.

History repeating: 2008-2018

A century and a half of economic data proves that when unions are strong the economy thrives. And when unions are weak, workers suffer. On the composite measure of labour market outcomes (chart 2), the present decade is second only to the 1930s as the worst on record, when trade union membership was at an equally low ebb.

Despite the lessons of history, politicians have once again sought to scapegoat trade unions for their own policy failures – with the 2016 Trade Union Act firmly part of the Conservative tradition of restricting the ability of workers to combine, strike and contribute to political parties.

And unfortunately, the dominant thinking in the economics profession still harks back to Ricardo, with society confined to ‘secular stagnation’ and dismal real wages a result of natural forces that workers must simply endure.

Lessons from history: 150 years of standing up for workers

Our hardest times in the past also provided cause for optimism, as the new thinking that came out of the 1930s offered a path to a better future.

‘No hope’ may be the default position of the dismal profession, but it was not the reaction of the governments and policymakers who overcame the Great Depression.

Nor was it the default position of the Attlee government, which created the NHS, provided education for all, built “homes for heroes”, strengthened the welfare state and nationalised several industries in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War.

Today, others – not least the Labour Party – are beginning to advance a new agenda for the future – an agenda that puts trade unions front and centre of our national economic strategy.

And even in the official arena, the new OECD ‘ jobs strategy’ has greatly moderated its language.

It recognises that flexibility-enhancing policies in product and labour markets are necessary but not sufficient. Policies and institutions that protect workers, foster inclusiveness and allow workers and firms to make the most of ongoing challenges are also needed to promote good outcomes.

The lesson from the past is that the decline of trade union membership is not inevitable.

Our history shows that retreat need not be the norm; that our movement can grow and succeed again.

So as the TUC celebrates 150 years of fighting for workers, here’s to another century and a half of making the working world a better place for everyone.

References

Dimitris P. Sotiropoulos and George Economakis ‘Trade Unions and the Wages Fund Theory: On the Significance of Mill’s Recantation and Some Notes on Marx’s Theoretical Intervention’, History of Economic Ideas, Vol. 16, No. 3., pp. 21-48.

OECD (1994) The OECD Jobs Study: Facts, Analysis, Strategies.

OECD (2018) Good Jobs for All in a Changing World of Work: The OECD Jobs Strategy

TUC (1968) The History of the T.U.C. 1868-1968 A Pictorial Survey of a Social Revolution

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox