Five takeaways from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings

Today the Office for National Statistics published its most authoritative assessment of pay in the UK – the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings – known as ASHE to its friends.

Here’s five takeaways from the figures.

1. The pay squeeze isn’t over

Average full-time weekly earnings rose faster last year than they have for a while – up 3.5 per cent in cash terms (on a weekly basis for full time workers), and 1.2 per cent when inflation (CPIH) is taken into account.

But we shouldn’t get too excited.

This is still well below the four per cent cash terms rises that were common before the financial crisis – and this slow growth means that pay still hasn’t caught up with where it was in 2008.

Few will be celebrating the fact that their pay is now worth what it was in 2011.

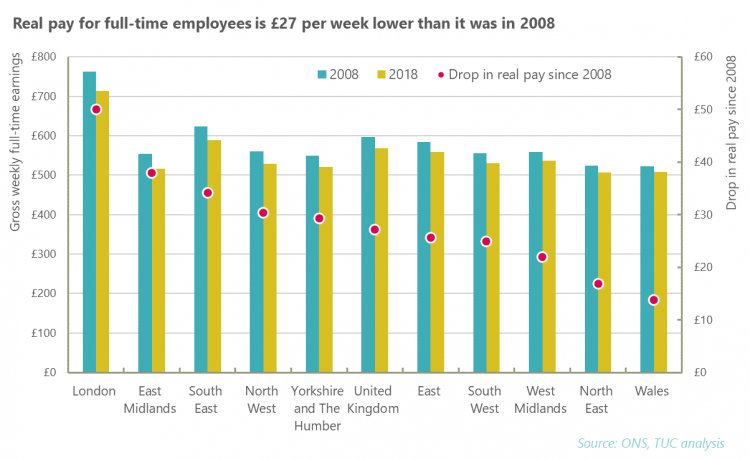

We also looked at average full-time weekly earnings in 2018 compared to 2008. When taking CPI inflation into account, they’re still around £27 (4.6%) below where they were before the recession. In some regions, the drop is much higher than this.

The average full-time employee working in the East Midlands is earnings around £38 less per week, and in London it’s a drop of around £50.

2. The rich are back to getting richer

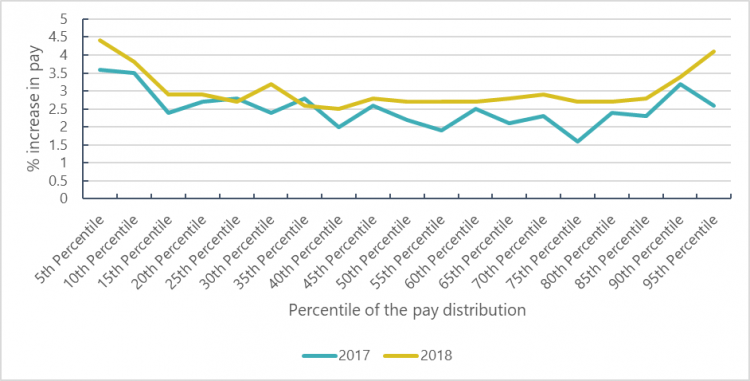

The last couple of years have seen a pattern of larger pay increases for the lowest paid, meaning a slow-down in the UK’s high level of pay inequality.

But it looks like last year increases at the top came back.

For full time workers, pay at the 95th percentile (that is, the top five per cent of earners) rose by 4.1 per cent – almost matching the National Minimum Wage driven increases for the bottom five per cent (4.4 per cent), and far outpacing pay growth for the average worker (pay at the 50th percentile went up by 2.7 per cent).

That pattern of increases means that pay inequality widened again – with weekly pay at the 90th percentile now 6.9 times higher than pay at the tenth (up from 6.7 per cent last year).

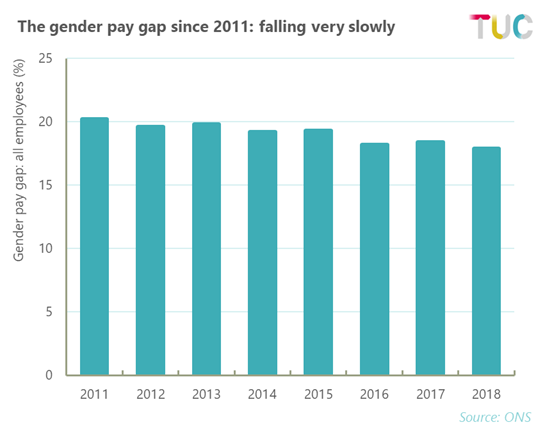

3. Progress on closing the gender pay gap is glacial

The gender pay gap for median earnings has fallen by 0.5 percentage points to 17.9% in 2018 (from 18.4% in 2017).

At this rate, another generation of women will spend their whole working lives waiting to be paid the same as men, with the pay gap eventually closing in 55 years – that’s 2073.

4. Raising the minimum wage is helping the lowest paid - but not fast enough

There was some good news in the figures – the proportion of low paid employees (measured as those falling below two thirds of median earnings - £8.52 in 2018) fell to its lowest level since the ONS started measuring this back in 1997.

That’s been driven by increases in the National Minimum Wage – a good sign that policy works.

But if we know this policy works we also know it could be working harder.

If we keep seeing low pay fall at the rate we saw last year, it will be another thirty years before we’ve finally eliminated it.

And the figures are a good reminder that it’s not just hourly pay that matters but the number of hours of work people are able to get.

On a weekly basis the number of low paid people is much higher – at just over 25 per cent.

5. But it looks like there’s a problem with underpayment

These figures give us a first estimate of how many people are paid below the minimum wage.

We have to be a bit careful with these numbers.

Some of the people who show up in them will be being cheated out of their proper wages by their employers.

But others may be legitimately paid a different rate, for example because they’re on an apprenticeship or training scheme.

And the fact that the survey is done at the same time as the national minimum wage goes up means that the increased rate might not have been applied when the survey was taken.

But the figures are still worrying.

In April 2018, ASHE indicates that there were 441,000 people paid below the relevant national minimum wage or living wage rate – a significant rise from the 419,000 people in this situation last year.

Britain’s pay squeeze isn’t over yet, and too many people are low paid.

Next week’s Budget is a chance for the Chancellor to start addressing those problems.

Britain still deserves a pay rise.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox